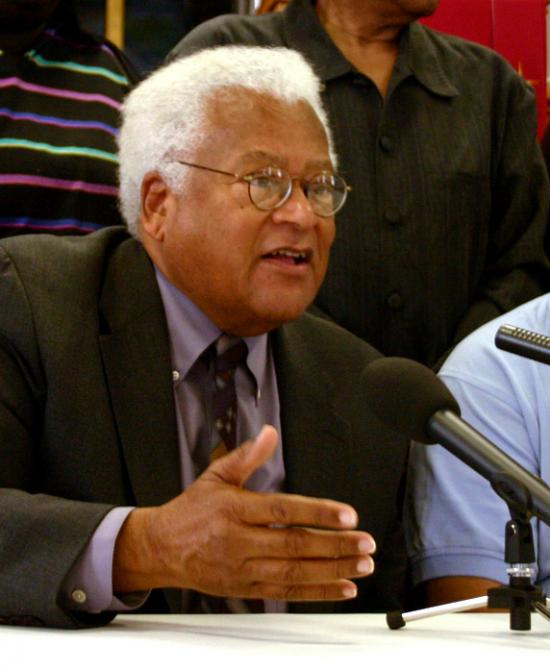

James Lawson, who died in June aged 95, was described by Martin Luther King Jr. as ‘the greatest teacher of nonviolence in America.’

Best known for his activism during the US civil rights movement, Lawson travelled to the then segregated city of Nashville, Tennessee in the late 1950s, after King implored him to join the struggle.

Heavily influenced by Gandhi and working as a field secretary for the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), Lawson started running regular workshops on nonviolence in a church basement, vowing to turn Nashville into a ‘laboratory for demonstrating nonviolence.’

Keeping with the science analogy, US historian Taylor Branch notes in his 1988 book Parting The Waters: American in the King Years, 1954-63 that Lawson approached nonviolent struggle ‘with the care of a chemist. Each step was planned, executed, and evaluated, with an eye toward isolating behaviour and controlling response.’

Over several months, workshop attendees – largely young students including people who would become central figures in the civil rights movement such as Diane Nash, John Lewis and James Bevel – were educated about the history of nonviolent action. They discussed and decided on the overall aim of the campaign, their tactics and target – desegregation of the city, and sit-ins at the segregated lunch counters of downtown department stores, respectively. In preparation Lawson led role-playing training sessions, simulating the verbal abuse and violence the activists would invariably receive during their planned civil disobedience.

In Waging A Good War: A Military History Of The Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1968 (PN 2665) Thomas E Ricks highlights the similarity between Lawson’s strategy and tactics and those employed by the military. For example, he organised reconnaissance missions in late 1959, with activists dispatched to conduct dry runs at lunch counters. On being refused service, they politely asked to speak to the manager to hear an explanation of the store’s policy, before reporting back to Lawson what they had experienced. Following similar sit-ins in Greensboro, North Carolina, the Nashville campaign began in February 1960, with over 120 students walking downtown, in their smart church clothes, for sit-ins at three lunch counters – ‘the civil rights equivalent of paratroopers – an elite force of volunteers, well trained and highly motivated,’ argues Ricks.

Each group had a leader, with observers reporting back to the campaign headquarters via runners. When the violence and arrests began after two weeks of sit-ins the campaign’s efficient communications and logistical systems meant they were able to quickly replace those activists at the lunch counters who had been taken away by the police.

‘The protestors welcomed jail,’ treating it as an opportunity, Ricks notes. ‘They organized their days with set periods of sermons, lectures, and quiet time… it became a bonding experience’.

With tensions rising in the city, the campaigners decided to escalate, calling for a boycott of segregated department stores to run alongside the continuing sit-ins. A majority of the Black community observed the boycott, while many white people stayed away from the downtown area because of the protests.

According to Ricks, Lawson believed nonviolence was much more confrontational than passive, and that ‘one must never be passive about absorbing violence’. An attack always required a response. ‘The idea was to take the release of destructive energy and recycle it into a positive action.’

So when the house of a prominent Black Nashville city councillor was bombed in April 1960, a march was quickly organised. Over 2,500 students from Black colleges walked, in silence, and in ranks of three, to the city hall demanding a meeting with the mayor. During an exchange with Nash on the steps of the building, the mayor agreed the lunch counters should be desegregated, thus beginning the desegregation of Nashville, which would take several years to complete.

Speaking about attending Lawson’s workshops, activist Bernard Lafayette said ‘We were warriors. We had been prepared. This was like a nonviolent academy equivalent to [elite US military] West Point.’

As one of the most famous chapters in the US civil rights struggle, two essential documentary series – 1987’s Eyes on the Prize: America's Civil Rights Movement and 1999’s A Force More Powerful – devote episodes to the Nashville campaign. The workshops and sit-ins are also represented in the 2013 Hollywood blockbuster film The Butler.

Born in 1928, Lawson grew up in Massillon, Ohio. He became a Methodist minister during his senior year in school (his father and grandfather were also Methodist ministers). Exposed to the work of pacifist AJ Muste and movement organiser Bayard Rustin in college, in 1951 he was sentenced to three years in prison for refusing the Korean War draft, serving 13 months.

Soon after, he travelled to Nagpur in India to work as a missionary and study the mass civil disobedience independence campaign led by Gandhi.

As well as his work in Nashville, Lawson was an inspirational mainstay of the wider civil rights movement, assisting with the school desegregation campaign in Little Rock, Arkansas and delivering nonviolence training during the 1963 struggle to desegregate Birmingham, Alabama. Helping to coordinate the Freedom Rides in 1961, he even held a workshop on nonviolence inside one of the buses after it was attacked in Montgomery, according to Kent Wong in the recently published book Revolutionary Nonviolence: Organising for Freedom (see Gabriel Carlyle’s review in PN 2673).

Lawson was involved in establishing the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an influential civil rights group, and also served as director of nonviolent education for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. And in 1968 he played a central role in the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike, inviting King to the Tennessee city to support the industrial action (King was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis).

In 1974, Lawson moved to Los Angeles, becoming pastor at Holman United Methodist Church, continuing to hold regular nonviolence workshops. He was active on various progressive causes over many decades, including labour campaigns, opposition to US intervention in Central America and advising Occupy activists in 2011. In 2000, he took part in a FoR peace delegation to Iraq to protest the US-UK-led economic sanctions that were devastating the Middle East nation.

A renowned practitioner and strategist of nonviolent action, Lawson’s influence on activists and movements has been huge.

As well as directly inspiring key figures in the US civil rights struggle such as Nash, Lewis and SNCC, professor Erica Chenoweth, who has arguably done more to promote the efficacy of nonviolent struggle than any other academic in recent times, considers Lawson to be a mentor.

Moreover, Lawson’s impact can be seen in the work of grassroots activist groups in the UK today, including Extinction Rebellion and Just Stop Oil. These two organisations’ interest in experimenting to see what works, their willingness to be imprisoned and their after-action evaluations closely echo the Nashville campaign. (Roger Hallam, the co-founder of both groups, is a keen student of the US civil rights movement.)

Nearing the end of his life, Lawson said his ‘fundamental message’ for the next century was ‘the US must experience a series of nonviolent campaigns that will make what we did in the 20th century look tiny and small and calm in comparison.’