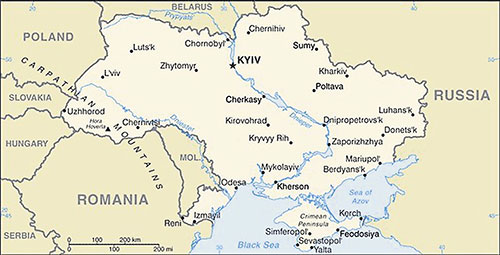

There are two connected Ukraine crises going on. There is a civil war in Eastern Ukraine, in the Russian-speaking Donbass region, which Russia is involved in. There is also a larger confrontation over NATO expansion. The massing of over 100,000 Russian soldiers on the border and the threat of all-out war are linked to both crises.

As we go to press, it’s not clear what is going to happen.

What is clear is that there are nonviolent solutions to both crises.

Solving the internal crisis

Russia specialist Anatol Lieven points out that there is already a solution to the Donbass crisis. It was negotiated and accepted by France, Germany, Russia and Ukraine in February 2015. It was adopted that same month by the UN security council, unanimously.

It’s called the Minsk II Protocol and it would mean restoring Ukrainian government control over both the breakaway Donbass region and the border with Russia. It would also give Donbass full, permanent autonomy within a decentralised, federal Ukraine.

Under the protocol, Donbass would be demilitarised, with no Ukrainian soldiers there for a while, the withdrawal of all Russian military ‘volunteers’, and the disarmament and demobilisation of pro-Russian militias.

Why hasn’t Minsk II been put into action? Because the Ukrainian government has refused to take the first steps outlined in the agreement.

‘It is possible that in future the Russian government and separatists would sabotage a peace settlement based on Minsk II. It is certain that, up to now, it is the Ukrainian side that has done so – without criticism or repercussions from U.S. administrations.’ Those are the words of Anatol Lieven, who covered Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union for the The Times in the 1990s

That’s from a report Lieven wrote in January for the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft in the US, where he is a senior research fellow.

His conclusion is that putting Minsk II into action will ‘take intensive pressure by the United States and its allies on Ukraine as well as Russia; for since 2015 Ukrainian governments and parliaments have refused to take the essential first steps to its implementation.’ That means pressure by Britain as well.

In terms of internal Ukraine problems, that would leave the Russian occupation of Crimea, which was ‘legitimised’ by a referendum held under Russian control. Some have suggested holding a proper referendum under UN control on the future of the territory as a possible solution.

(Maybe we can be the first to suggest holding a UN referendum in Guantánamo province, Cuba, on the future of the territory occupied there by the US: the Guantánamo Bay base?)

‘Not one inch’

Solving the larger confrontation between NATO and Russia in Eastern Europe is a much more difficult problem, but the first step is fairly clear.

It would mean, in the words of Noam Chomsky, all sides accepting ‘Austrian-style neutrality for Ukraine, which means no military alliances or foreign military bases’ (along with a demilitarised, federal solution internally, along the lines of the Minsk II agreement).

There is a bigger picture.

Russia says, correctly, that NATO leaders have gone back on guarantees they offered in 1990 that NATO would move ‘not one inch’ to the east if the Soviet Union allowed East Germany to reunite with West Germany as part of NATO.

Allowing a reunified Germany to be a NATO member was, as Chomsky told Truthout in December, ‘a remarkable concession by Russia, considering that Germany alone, not part of a hostile military alliance, had virtually destroyed Russia twice in the past century, a third time joining with the West (including the US), in the “intervention” immediately after the Bolsheviks took power.’

The ‘not one inch’ quote comes from a meeting on 9 February 1990 with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. The then US secretary of state, James Baker said: ‘not only for the Soviet Union but for other European countries as well it is important to have guarantees that if the United States keeps its presence in Germany within the framework of NATO, not an inch of NATO’s present military jurisdiction will spread in an eastern direction.’

There are those who say that Baker was just talking about NATO not expanding into East Germany, but nowhere does Baker mention ‘East Germany’ or ‘the GDR’ (the official name of East Germany). Baker talked generally about ‘assurances that there would be no extension of NATO’s current jurisdiction eastward’.

It wasn’t just Baker either.

Many Western leaders told Gorbachev in 1990 that, after German reunification, they would help to create an inclusive security structure for Europe which didn’t threaten Russia’s interests.

The day after Baker’s meeting, for example, on 10 February 1990, German chancellor Helmut Kohl told Gorbachev: ‘We believe that NATO should not expand the sphere of its activity.’

Baker said to Gorbachev on 18 May 1990: ‘Before saying a few words about the German issue, I wanted to emphasise that our policies are not aimed at separating Eastern Europe from the Soviet Union.’

Instead, NATO has taken Eastern European states as members and there are now US, UK, German, French, Dutch and Canadian troops in Romania, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Bulgaria. There is a US ‘Aegis Ashore’ missile base in Romania and another one due to come into operation in Poland this year.