This is not so much a biography as one well-informed radical’s readable take on modern world history (with a lot of attention paid to the Russian Revolution – Trotsky is quoted frequently). The figure of Winston Churchill is mostly just a hook Tariq Ali uses to hang some eye-opening stories on.

If you want a thorough, sceptical, myth-busting account of the life of Winston Churchill, search out Clive Ponting’s 876-page Churchill (out of print).

Ponting’s attention to detail is remarkable. For example: ‘Churchill’s finances had been transformed during the [Second World] war – exactly how is not known, although one helpful development was that the Inland Revenue secretly wrote off all his outstanding taxes. By early 1946 he had £120,000 in the bank...’ – a sum worth well over £5mn in 2021.

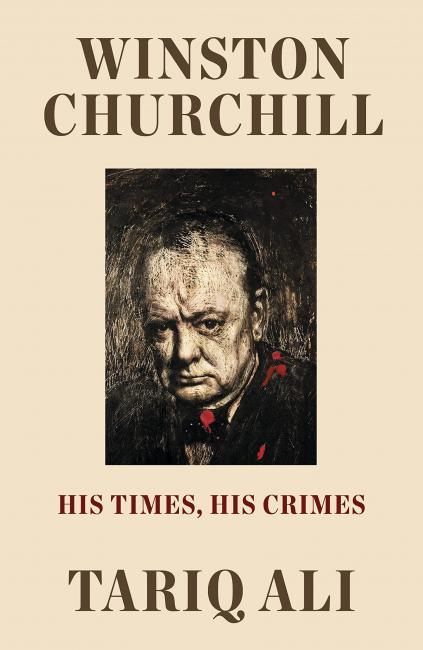

Tariq Ali is very clear that this kind of biography is not his goal. He uses the opening chapter of Winston Churchill: His Times, His Crimes to survey the state of European colonialism in 1874, the year when Churchill was born. Over half the second chapter is about Britain’s Chartist movement – which had disintegrated well over a decade before Churchill was born.

Alongside a selection of historical struggles not very connected to Churchill, there are also many of his crimes.

These include his use of troops against Welsh miners in 1910 and the disastrous Battle of Gallipoli in 1915 (‘the one major initiative undertaken by Churchill’ during the First World War).

There is a long, painful description of the British conquest of Greece starting in 1944 – after the Nazis had withdrawn. Ali comments, accurately: ‘The most successful Resistance in Europe was snuffed out by Churchill and the British Army in one of the bloodiest moments of the war.’

The most powerful section, and possibly the most personal, tells the story of the 1942 – 1944 Bengal famine in India.

Starvation and disease killed ‘between 3.5 and 5 million people’, Ali writes.

Ali notes that the local harvest in 1943 was only five percent less than in previous years, but ‘crucial food supplies were diverted to the war effort’, on Churchill’s orders, to feed soldiers and factory workers engaged in war production. Rice was also confiscated and boats destroyed by the British military – to deny them to the Japanese forces expected at any moment.