In 1876, Russian general Mikhail Skobolev defeated and subdued the khanate of Kokand based in present-day Uzbekistan, an important moment in cementing tsarist imperial control of Central Asia. Appalled at the nationalistic celebrations that greeted this in Russia, Leo Tolstoy penned his remarkable text The Kingdom of God is Within You. ‘Why do good men and even women,’ he lamented, ‘quite unconnected with military matters, go into raptures over the various exploits of Skobelev and other generals?’ Pitting an anarchist vision of Christian pacifism as an alternative to state violence, Tolstoy’s book would become one of the most influential works in the global peace movement, directly influencing Gandhi (with whom Tolstoy corresponded), Martin Luther King Jr, and others.

Sadly, ‘raptures’ over military violence show no sign of disappearing from Europe any time soon, as the Russian invasion of Ukraine shows.

War fever has gripped both Russia and Ukraine as their populations have generally supported their belligerent presidents. These raptures have spread much further.

Across the West, for example, Ukrainian flags are emblazoned over social media and public space. Massive amounts of military aid have been provided or promised to Ukraine, and war-porn videos of Ukrainian soldiers using these weapons to kill Russians have been widely and approvingly shared online. The power of war to send otherwise apparently sane people into raptures seems as great today as it did in the 1880s.

But war fever is not inevitable. Before wars can be fought they have to be thought, and to dissipate war fever we need to rethink our vision of Europe from one of rival blocs to one of a demilitarised space of peace. Part of doing that is to question the role that NATO expansion has had in bringing about the current Russo-Ukrainian war.

Geopolitical visions

I am a political geographer, and my discipline has the dubious distinction of giving birth to ‘geopolitics’. This is the idea that you can explain and predict global politics by understanding the objective geography of the world. It appeals to right-wing thinkers who erase real people from their analyses and reduce complexities to simple geographical formulas – such as ‘East vs West,’ or ‘the clash of civilisations’ – in order to justify military interventions.

In recent years, however, the field of ‘critical geopolitics’ has emerged. The vital insight here is that the ways that political actors think about global space reflect not objective realities but rather their subjective beliefs, and then these geopolitical visions in turn affect the ways that they act in the world.

For example, if you see enemies everywhere and act accordingly (by building military blocs to counter them) then you will be more likely to arouse suspicion, intensify hostility and provoke conflict. On the contrary, you are more likely to create peace if you seek to reach out co-operatively to others.

The value of this insight can be demonstrated by the role of NATO enlargement in bringing about the present Russo-Ukrainian war.

Headquartered in Brussels, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation was formed in 1949 allegedly to ‘promote stability and well-being in the North Atlantic area’ through ‘collective defence and for the preservation of peace.’

“The United States and its allies should abandon their plan to Westernize Ukraine and instead aim to make it a neutral buffer between NATO and Russia, akin to Austria’s position during the Cold War.” - John Mearsheimer

The word ‘defence’ here is dishonest: NATO structures and forces have been used on several occasions to suppress anti-colonial resistance movements and to attack or occupy countries well outside ‘the North Atlantic area’ across Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

But NATO was never just an aggressive military alliance. It was also one of the main tools used by the US to assert and maintain its dominance after the Second World War. NATO ‘justified’ the stationing of vast numbers of US troops in Europe after the defeat of Hitler, the reason for their arrival on the Continent. Lord Ismay, NATO’s first general secretary, said that the purpose of NATO was ‘to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.’

Because NATO was formed mainly to counter the Soviet Union, its reason for being seemed to evaporate with the end of the Cold War. Many European intellectuals and leaders argued for the creation of new collaborative systems of European security that would replace Cold War structures.

Yet, rather than winding up the alliance, the US was soon pushing for NATO’s expansion. Why was this?

Enlargement

US president George Bush Snr’s administration (1989 – 1993) didn’t pursue NATO expansion because it had promised Russian leader Mikhail Gorbachev not to expand NATO ‘one inch East’ if Russia allowed a united Germany to be part of the alliance.

However, pressure for NATO enlargement grew from a number of sources after the Democratic capture of the White House by Bill Clinton in 1993, argues Haluk Dogan, a PhD student in Strategy and Security at Exeter university. Hawks in the Republican party were concerned that the end of the Soviet threat removed the justification for the massive US military presence in Europe. They pushed for Clinton to backtrack on Bush’s promises. Leaders of Central European states petitioned the new president for NATO membership as a guarantee against any future threat from Russia. Their diaspora organisations in the US were very effective at lobbying US politicians. Similarly, US military contractors saw an opportunity to sell hardware to East European states if they joined the alliance, with Lockheed Martin’s Bruce Jackson founding the Committee to Expand NATO in order to lobby congress. At the same time, pro-Western factions of Russia’s elite, headed by Boris Yeltsin, softened their opposition to NATO expansion.

These pressures culminated in the passing of the NATO Enlargement Facilitation Act by both houses of congress in 1996.

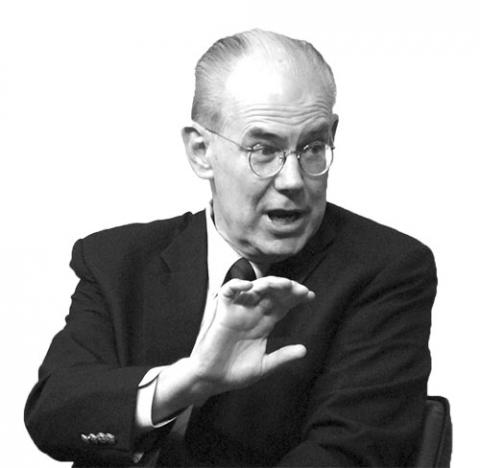

There was far from universal support in the West for this, however, as represented by a striking public intervention from retired US diplomat George Kennan. In 1997, aged 92, he wrote in the New York Times that ‘expanding NATO would be the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-cold-war era.’ Kennan regarded NATO expansion as both unnecessary (because Russia posed no apparent threat to the US) and unfortunate (in that it would squander the ‘hopeful possibilities engendered by the end of the cold war’).

Kennan warned that NATO expansion would have a number of negative consequences: inflaming ‘nationalistic, anti-Western and militaristic tendencies’ in Russia; hampering ‘the development of Russian democracy’; restoring the ‘atmosphere of the cold war to East-West relations’; hindering nuclear weaponry reduction negotiations; and pushing Russian foreign policy ‘in directions decidedly not to our liking’.However, Kennan’s warnings went unheeded.

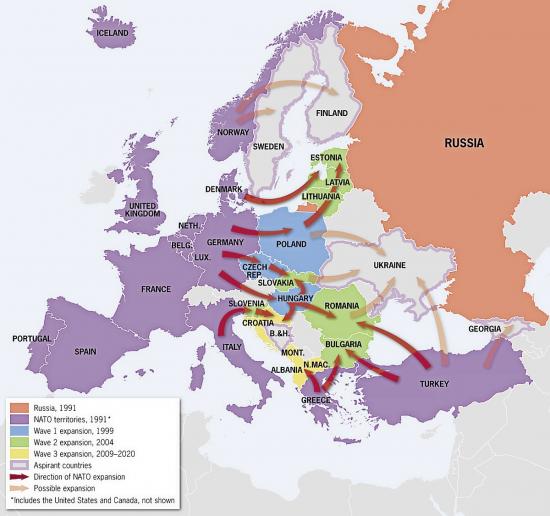

NATO expanded eastwards in three waves which drew increasingly closer to Russia (see map). A turning point was the alliance’s 2008 Bucharest summit, which declared that ‘NATO welcomes Ukraine’s and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations for membership in NATO’ and ‘agreed today that these countries will become members of NATO.’

Kennan’s argument was restated by the prominent international relations thinker John Mearsheimer in a 2014 Foreign Affairs article on ‘Why the Ukraine crisis is the West’s fault.’ Mearsheimer argued that NATO enlargement, EU expansion and democracy promotion were seen by Russian president Vladimir Putin as a threat to Russia but, because of ‘liberal delusions’ about the supposedly inevitable triumph of post-Cold War neoliberal democracy, this was not recognised by Washington.

In 2013, when elected Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych opted for a more lucrative Russian economic deal over an EU one, violent demonstrations led to his ousting and the installation of a pro-Western, anti-Russian government. This, declared Mearsheimer, triggered Russia’s decision in 2014 to annex Crimea and launch a destabilising intervention in east Ukraine. NATO’s response, promising increased military aid, ‘will only make a bad situation worse’, Mearsheimer predicted. The way out, he suggested, would be for the US and its allies to ‘abandon their plans to westernise Ukraine’ and instead ‘aim to make it a neutral buffer between NATO and Russia,’ boosted by a joint Russian, US, IMF and EU economic development plan.

More than one ‘vector’

Kennan’s and Mearsheimer’s warnings were startlingly far-sighted. Almost everything they feared about the effects of NATO expansion has come to pass. To some people, it should be said, their arguments are suspect because some aspects of what they said have been put forward in Russian justifications for the most recent invasion of Ukraine.

However, the fact that their analyses and criticisms were later echoed in Kremlin propaganda cannot be a criticism of their writing. Trying to understand and explain dangerous geopolitical reasoning should in no way be confused with justifying it.

The real problem with Kennan and Mearsheimer’s positions, rather, is that they do not address local agency, the wishes and intentions of Ukrainians, and their ability to seek and make changes to further what they see as their own interests.

“Expanding NATO would be the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-cold-war era” - George F Kennan

For Mearsheimer, Ukraine is just a potential ‘buffer zone’ in someone else’s geopolitical game. In reality, many political elites in Eastern Europe actively sought membership of NATO and the EU as forms of protection against the main threat to their existence in modern times – Russia.

This weakness does not overturn the overall argument that NATO expansion is a significant element in the present war.

What matters is the perception of threat in Russia and how political actors in Brussels, Kyiv and Washington DC understand and respond to it.

In 2014, Russia’s foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, gave a major foreign policy speech on the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall – it was actually about explaining Russia’s logic in Ukraine. Like Kennan, Lavrov lamented that ‘the chance to overcome the dark legacy of the previous era, and decisively erase the dividing lines was missed.’ He blamed Western expansionism, including the EU but particularly NATO, for this.

‘Assurances that the North Atlantic Alliance would not expand eastward – which had been given to the leadership of the Soviet Union,’ Lavrov claimed, ‘turned out to be empty words, for NATO’s infrastructure has continuously drawn closer to Russian borders’ (as the map shows).

Lavrov went on to say that Russia had repeatedly warned that Ukraine should not be forced to ‘choose one vector of its foreign policy…’ (in other words, to clearly align itself with either Russian or Western foreign policy structures). He went on: ‘We were not heard.’

A proxy war?

At an April 1997 senate hearing, then US secretary of state Madeline Albright said this, in defence of the Clinton administration’s plans for NATO expansion:

‘A “New NATO” can do for Europe’s east what the old NATO did for Europe’s west: vanquish old hatreds, promote integration, create a secure environment for prosperity, and deter violence in the region where two world wars and the Cold War began.’

If this truly was the aim of US foreign policy, then it has failed spectacularly in every respect. NATO expansion has certainly furthered the unstated goal of maintaining US armed forces in Europe, but it has made the continent less safe and has brought about its most destructive war since 1945.

However, wars are rarely caused by just one factor. Ukrainians who criticise left-wing western commentary that pins more blame on the West than Russia are right. That is why a coalition of peace and anti-war groups in the UK use this slogan: ‘Russian Troops Out! No to NATO Expansion!’ This wording recognises both the immediate responsibility of Russia for the crime of this war and also the indirect responsibility of NATO. It points to a more peaceful approach to finding a way out of the current conflict and towards a more sustainable peace.

The Ukraine War is increasingly looking like a proxy war between NATO and Russia. At the time of writing, NATO members are almost daily promising transfers or sales of more and more advanced weaponry to Ukraine, which has asked for this to help repel the Russian invasion.

Hawkish US and UK officials have spoken of their goal being long-term geopolitical advantage over Russia. For example, US national security adviser Jake Sullivan admitted that the US’s goal was to see not just ‘a free and independent Ukraine,’ but also ‘a weakened and isolated Russia, and a stronger, more unified, more determined West.’

While the defence of Ukraine might be morally justifiable, we have repeatedly seen such proxy wars drag on for years, cause horrendous suffering to the places over which they are fought, and have unintended negative consequences for decades to come.

With other countries seeking NATO membership to protect themselves from similar Russian aggression, one of these consequences could be a wider escalation of violence. NATO expansion is the very problem whose solution it claims to be.That escalation could even be nuclear.

Theatre of peace, not war

In the 1970s, the UK government prepared a ludicrous public information campaign, ‘Protect and Survive,’ advising the population on how to ‘protect’ themselves from nuclear attack and ‘survive’ the subsequent destruction.

In response, in 1980, leading radical historian and peace activist EP Thompson edited the pointedly-titled Protest and Survive. Thompson was a founder of the pan-European peace movement, European Nuclear Disarmament (END). Recognising that war fever on both sides of the ‘iron curtain’ threatened the peace and survival of Europe, END sought to work for a demilitarised Europe free of both Soviet and US weapons of mass destruction.

Thompson was part of an activist network that overcame the East-West divide. As historians have claimed, this network had a significant role in influencing European security thinking and ensuring that the Cold War ended without the violent conflagration that so many had feared.

Thompson wrote: ‘Against a strategy which envisages Europe as a “theatre” of limited nuclear warfare, we propose to make in Europe a theatre of peace’. In galvanising a loose network of scholars, pastors and activists across Europe, he showed how this could be done. This was a critical geopolitics of peace put into practice. As END’s Appeal for Nuclear Disarmament put it: ‘We must commence to act as if a united, neutral and pacific Europe already exists.’ For Thompson, this involved creating new loyalties and disregarding ‘the prohibitions and limitations imposed by any national state’.

This is the kind of peaceful reimagining of Europe that is required today.

We need a Europe where divisive military alliances like NATO are consigned to the dustbin of history.

We need a Europe where the dangerous pretensions of rival blocs like the European Union and the Eurasian Economic Union are tamed or transcended.

We need a Europe where majority populations and ethnic/linguistic minorities alike are protected from invasion and discriminatory state coercion.

We need a Europe of collective security guarantees from the Arctic to the Mediterranean, from the Atlantic to the Urals – and beyond.

We need a Europe of citizens whose loyalty to each other is more powerful than the lurid raptures of war fever.

We need a Europe which Tolstoy would recognise as an improvement over the one he witnessed in the 1880s.

Due to the catastrophic decision to expand NATO, we missed the chance to create such a Europe in the 1990s. As a result, it will be harder to build such a Europe now, as proper peace demands restitution and accountability for the horrendous injustices inflicted upon Ukraine by Russia. Rebuilding lost trust will be hard. But we can still do it, and in so doing open a negotiated way out of the current disaster.