Among the first books I read when I got involved in the peace movement in the late 1990s, three were by Michael Randle: Civil resistance (on the history, theory and practice of nonviolence), How to defend yourself in court (a useful instructional) and The Blake Escape (co-authored with Pat Pottle, their thrilling account of how and why they helped to break superspy George Blake out of Wormwood Scrubs prison and smuggle him out of the country).

Unhappily all three of these excellent works now appear to be out of print.

But, on the plus side, we now have two new books that illustrate, update and explore some of these books’ major themes.

Though perhaps now best known to the general public for his involvement in the Blake escape, Randle is also one of the most dynamic figures of the postwar British peace movement. Even a partial record of his exploits is incredibly impressive.

From his one-person 1956 peace walk from Vienna to Budapest (in response to the Soviet invasion of Hungary) and his work helping to organise the first march from London to the Atomic Weapons Establishment at Aldermaston, to his involvement in the 1959 protests against French ‘nuclear imperialism’ in Africa (the Sahara Protest Teams) and his pivotal role in the anti-nuclear Committee of 100 (for which he received an 18-month jail sentence)....

From helping to co-ordinate simultaneous international demos for War Resisters International in 1968 (opposing the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia) and helping Czech dissidents to smuggle duplicators into their country, to serving an additional eight months in prison for taking part in an occupation of the Greek embassy in London (following the colonels’ coup in 1967) and co-ordinating the Alternative Defence Commission from 1980 – 1988 (which produced the groundbreaking report Defence Without the Bomb)....

Perhaps the most remarkable fact of all is that he embarked on this whirlwind of activity almost immediately upon leaving school at the age of 16! (It wasn’t until he was in prison in 1962 – 1963 that Randle was able to get his A-levels, opening the door for him to attend university following his release.)

Peace News plays a significant role in the story. Indeed, Martin Levy notes in Ban the Bomb!, it was reading an article in PN (in the 18 January 1952 issue) that changed Randle’s life and drew him into nonviolent direct action.

Beginning with Randle’s birth in 1933, Levy covers all of these activities and more in his wonderful new book, which is made up of an edited series of interviews with Randle.

In the book’s foreword, Paul Rogers writes that Ban the Bomb! provides a picture ‘not just of Michael but of the history of nonviolent action in Britain over seven decades’, bringing us ‘into contact with many of the leading campaigners and thinkers on nonviolence over those decades’. Among other things, we see the cross-pollination and connections between the UK peace movement and its counterparts in the US, France and elsewhere.

For example, the gay African-American pacifist Bayard Rustin – an important figure in the US civil rights movement – spoke in Trafalgar Square at the outset of the first Aldermaston March, and was subsequently involved in Project Sahara, alongside Randle.

There are also some striking similarities between the UK’s anti-nuclear direct action movement of the late 1950s and early 1960s and the recent history of Extinction Rebellion.

For example, both groups showed tremendous chutzpah, generated mass arrests (around 1,300 people were arrested at the Committee of 100’s nonviolent protest in Trafalgar Square on 17 September 1961) and met government ministers.

Both groups raised huge existential issues while arguably displaying a degree of naivety about how much change their chosen strategy and tactics were likely to achieve. (Looking back, Randle concedes that ‘ideology overtook reality.… We still had this idea of a popular uprising that would change everything. But things never got to the stage of ferment where that could have happened.’)

And both groups involved a highly-polarising figure – catnip to some, anathema to others.

In the final chapter (which I’m guessing was probably conducted in 2019), Randle shows himself, well into his 80s, still actively thinking about the issues that have dominated his life.

He says that he is still ‘pretty much’ a pacifist, if not an ‘absolute’ one: ‘In the 1990s, I argued that you could protect vulnerable minorities by non-violent forms of action. Now, I’m not convinced this is always possible or likely to be efficacious. There are certainly situations in which it will not be effective’.

A librarian at the University of Bradford, Levy has done his background research and it shows. The book concludes with a wonderfully detailed ‘Chronology’ as well as a useful index.

It does assume a certain level of familiarity with the era, its events and personalities – or at least a willingness to look them up. (I suspect that many younger readers won’t know who Donald Soper or AJ Muste are.)

However, this is a relatively small issue for a book that is both a fascinating read and a huge pleasure.

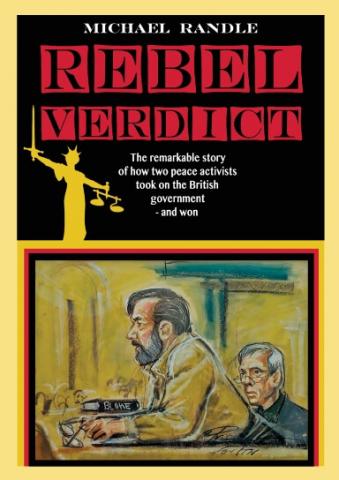

Levy’s book devotes a chapter to the Blake trial: Randle and Pottle’s 1991 trial for their role in the Blake escape. But this is now also the subject of a gripping 500-page book by Michael Randle himself: Rebel Verdict.

It’s an incredible story.

Randle and Pottle met Blake for the first time in Wormwood Scrubs prison in 1962; they were there for their peace movement activities. Though neither had any sympathy for spies of any stripe, they were both horrified by Blake’s 42-year sentence.

Following their release, the pair therefore conspired with an Irish prisoner, Sean Bourke, to break Blake out of prison and spirit him out of of the country to the Eastern bloc, on humanitarian grounds.

They succeeded, but only through series of near-miracles.

For example, at one point when Blake was hiding-out at Pottle’s flat, he ignored their agreed protocols and opened the door to a builder, who he then showed round the flat – notwithstanding the fact that his (ie Blake’s) face was in every paper and regularly appearing on television as the most wanted man in Britain!

This part of the story, which took place in 1966 – and is told at greater length in The Blake Escape – is recapped in the book’s first 40 pages, albeit supplemented with details that were not available when the former book was written.

In 1970 Bourke – now living in Ireland – published a book confessing to his role in the prison break, which also contained thinly-veiled descriptions of Randle and Potter (‘Michael Reynolds’ and ‘Pat Porter’). The police rapidly put two-and-two together, but a decision was apparently taken not to take any action against the pair at the time.

Indeed, it was not until a Sunday Times article was published in 1987, naming the pair, that a series of events was kickstarted that eventually led to their prosecution. As Pottle explained at the trial: ‘In 1970 it had been too embarassing to prosecute us. By 1989 it had become embarassing not to do so.’

Notwithstanding the intervening quarter-of-a-century, the pair faced substantial punishment if found guilty: a possible nine-year jail sentence, as well as the seizure-and-sale of their homes.

Nonetheless, they insisted on pleading not guilty and defending their actions in court.

They argued: firstly, that the whole trial was an abuse of process (because a decision not to prosecute them had been taken in 1970); secondly, that they had a legal defence of ‘necessity’ (‘the law had to be broken to achieve a greater amount of good’); and thirdly, that they had done the right thing.

The main body of Rebel Verdict concerns the entirety of the legal process: from their initial ‘outing’ and intial arrest in 1987 through to the trial in June 1991.

It is a complex story, rich in drama.

For example, at one point in the long lead-up to the trial itself a crucial MI5 document is revealed, leading the prosecution to tell Pottle, outside the court, that ‘You could well get away with it now.’

At another point, a witness gives evidence from behind a curtain – probably the first time that an MI5, or former MI5 officer had ever given evidence in open court.

At the trial itself, both defendants represented themselves, intending to exploit the leeway that a judge ‘might feel obliged to grant [them] as amateurs among professionals to put forward arguments and to question witnesses in a way not open’ to the latter.

Recognising this, the judge explicitly told them at the outset that they would ‘not have any [leeway] in this case’ – only to later lament (to the prosecutor) that: ‘notwithstanding the warning shot I fired earlier on we have given these two leeway we would never have allowed had they been represented. You have not jumped up and objected … and I have not intervened. There we are.’

Ultimately, the judge decided that the pair had no legal defence and all but directed the jury to find them guilty (‘Are we … sure that each defendant did the things the Crown say he did? If the inevitable answer is Yes, you will find the defendants guilty.’)

However, in his brilliant closing speech, Randle had told the jury: ‘The judge in rejecting our defence has stated that you must accept his ruling on a point of law. But in fact you have complete independence to act according to your conscience. If you come to the conclusion he is wrong, or that his ruling defies commonsense and humanity, you can ignore it. If you don’t have that freedom of action, if you simply have to follow the judge’s direction, what on earth have you been doing sitting here for the last ten days? Juries down the centuries have from time to time defied directions from judges and in doing so struck some of the most important blows for civil liberties, commonsense and humanity.’

To everyone’s surprise, the jury agreed and returned a unanimous verdict of not guilty on all counts.

This is a long, dense book. Clearly a labour of love, it provides a granular level of detail of the events it narrates: from the lunchtime adjournments in the early stages of the case, to Randle’s feverish desire to file his nails while he waits for the jury to return its verdict. In other hands, this could have resulted in a ponderous book. In fact, there is seldom a dull moment, much that is moving and quite a bit that is funny.

It’s true that some of the legal details of the pre-trial process went over my head (a glossary of some of the key terms might have helped). The 150 pages dealing with disclosure and the abuse of process arguments could probably be skimmed over by the more casual reader.

A timeline of the main events and a list of the key protagonists would have been very helpful. Ditto an index.

The most surprising fact, perhaps, is that this amazing story has not yet been turned into a verbatim play, along the lines of Richard Norton-Taylor’s The Colour of Justice.

In a moving coda, Randle relates how they were later able to track down one of the jury members and hear her account of why she had come to her decision.

In his final speech to the jury, Randle had referred to the jurors in the 17th-century case of Penn & Mead, two Quakers prosecuted for preaching in the street. (Their judge had directed them to find the pair guilty and when they refused had locked them up overnight ‘without meat, drink, fire or other accommodation’. When they still refused he had fined them each 40 marks and sent them to prison.)

Randle notes that ‘It is unlikely in the extreme that the members of [his and Pottle’s] jury will every have a plaque to them in the precincts of the Old Bailey as did the jurors in the … Penn and Mead [case]’.

Surely, this can and should be rectified.