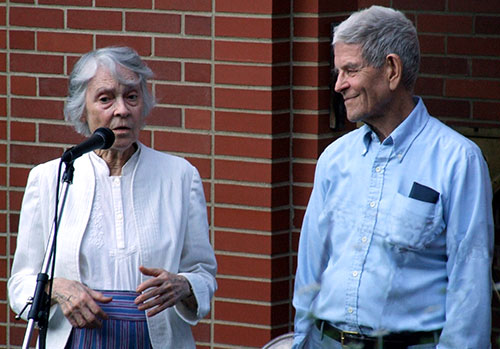

Staughton Lynd, who died last year, aged 92, may be one of the most important US activists you’ve never heard of.

A historian by training, Lynd played important roles in both the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements, before spending decades nurturing grassroots labour organisations and working in solidarity with prisoners locked up in so-called ‘supermax’ prisons.

“Perhaps the only person who could unite the New Left and Old Left, speak truth to power, and also be a persuasive advocate within the mainstream”

In the mid-1960s, one leading activist, the co-founder of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), Tom Hayden, thought Lynd was ‘perhaps the only person who could unite the New Left and Old Left, speak truth to power, and also be a persuasive advocate within the mainstream’.

But Lynd refused to take on such a role, finding himself increasingly at odds with both national organising and prevailing currents within the social movements of the time. Nonetheless, Hayden notes, Lynd ‘remained a leader of another sort, a leader from below, a leader in a process, a leader in thought’.

Burnham’s dilemma

In his teens, Lynd read James Burnham’s book The Managerial Revolution. Burnham noted that the European transition from feudalism to capitalism occurred because the bourgeoisie had been able to create capitalist institutions such as banks and corporations within feudal societies, only later taking state power.

Burnham claimed that there were no institutions that could play a similar role for a transition from capitalism to socialism. Trade unions smooth capitalism’s rough edges but don’t challenge capitalism itself.

The search for a solution to this problem – which he called ‘Burnham’s dilemma’ – became one of the central preoccupations of Lynd’s life.

He eventually found a ‘partial answer’ in the Zapatista idea of Mandar Obedeciendo (‘govern by obeying’). This is the idea that, rather than taking state power, ‘our Movement should create a horizontal network of self-governing institutions, strong enough that whoever holds the highest offices of government will be accountable to … “the below”, that is, to us.’

Freedom Schools

Born in 1929, Lynd decided very young that he ‘would never be a soldier’. He was a conscientious objector during the Korean War. With his wife Alice, Lynd spent three years in the mid-1950s living in a utopian community in Georgia, before returning to academia. Drawn to the civil rights movement, he took up a position at Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia, then a college for African-American women.

In 1963, Lynd was asked to co-ordinate the ‘Freedom Schools’, part of ‘Freedom Summer’, the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project. The latter, one of the iconic events of the civil rights movement, sought to register Black Mississippians to vote, in a state where violence and intimidation meant that only a tiny handful of African-Americans were registered.

The Freedom Schools were voluntary summer programmes for African-American teenagers where young people could experience some of the education and ideas denied to them by the segregated schooling system.

When Lynd asked sit-in veteran Harold Bardonille to co-coordinate the project with him, Bardonille visited Mississippi to check things out. ‘People are going to get killed there this summer’, he correctly predicted.

The three civil rights workers murdered on the eve of Freedom Summer – James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner – were abducted and killed while looking for an alternative site for a Freedom School. The initial site – a church – had been burned down.

Nonetheless, over 40 ‘schools’ were created, with an estimated 2,000 students participating. Lesson plans tackled African and African-American history, but also covered writers such as James Joyce, Jean-Paul Sartre and ee cummings.

In the city of Shaw, where students had to pick cotton in the summer, the curriculum was expanded to include nonviolent protest. The residents of Shaw went on to organise a cotton-pickers’ trade union and to take over their local school board.

The year after Freedom Summer, at the 1964 Democratic party national convention, civil rights activists attempted to have delegates from the recently-formed Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) seated in place of delegates from the all-white Mississippi Democratic Party.

Despite the fact that the MFDP had 80,000 members and infinitely more democratic legitimacy, the unions colluded with the party leadership to prevent this from happening.

For Lynd, historian Carl Mirra notes, this betrayal ‘signified the absolute failure of coalition-style politics and reinforced his allegiance to alternative institutions and to local organising over national coalitions’.

Vietnam

The main focus of Lynd’s activism now shifted to opposing America’s rapidly-escalating war in Vietnam.

In 1965, he played a key role in organising the first major protest against the war. The April march drew some 15,000 – 20,000 people, making it the largest single peace protest in US history up to that point!

It was followed, in August, by the Assembly of Unrepresented People, timed to coincide with the 20th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

A famous photograph from the day shows Lynd, flanked by legendary pacifist Dave Dellinger and civil rights icon Bob Moses on their way to the Capitol, splattered with red paint which had been hurled at them by a counter-demonstrator. (The photo appears on the cover of Lynd’s 2023 book, My Country is the World.) Moses and Lynd were both arrested at the protest.

In December 1965, Lynd was part of a three-person ‘people’s diplomacy’ delegation to Hanoi, the capital of North Vietnam.

In the words of fellow delegate Tom Hayden, the mission ‘broke the Iron curtain towards Vietnam’, paving the way for later visits by Jane Fonda, Howard Zinn and others.

But for Lynd this came at a cost.

Out of academia

In July 1964, Lynd had become an assistant professor of history at Yale university.

He soon found himself banned from from the profession,

Denied tenure at Yale on bogus grounds, Lynd would also have an offer of an associate professorship at Chicago State University withdrawn by its board of governors, citing his ‘public activities’.

In all, Lynd was denied appointment at five Illinois colleges and at least three colleges in Indiana.

In his 2009 joint memoir with his wife Alice, Stepping Stones, Lynd observed that: ‘It was acceptable for Yale faculty and alumni to manage the Bay of Pigs invasion for the CIA (Richard Bissell), repeatedly to advocate the invasion of North Vietnam (Walt Rostow), and to plan an unprovoked invasion of Iraq (Paul Wolfowitz). But it was unacceptable for me to be arrested on the steps of the Capitol in a symbolic effort to declare peace with the people of Vietnam, or to make an unauthorized trip to Hanoi.’

But he also reflected that he was ‘thankful not to have spent the past forty years as a history professor at Yale.… I have never stopped writing history. But because I was pushed from the academic nest, and became a lawyer, I have had an opportunity to come to know rank-and-file workers and death-sentenced prisoners that I never could have had as a university professor.’

Out of the Movement

After returning from Vietnam, Lynd became one of the most sought-after speakers in the social movements of the time. In the late ’60s, the Lynds moved to Chicago to become full-time participants in attempts to create ‘an interracial movement of the poor’.

But by then the prospects for building such a movement were rapidly receding.

At the same time, attitudes towards political violence and methods of organising were also changing.

In Stepping Stones, Lynd writes that he came to a realisation that ‘if I spoke out publicly against calling policemen “pigs” or against the creation of a Marxist-Leninist vanguard party, I would rapidly fade into movement obscurity.… I decided to go on believing what I had always believed and not to hide it. I did publicly oppose calling police officers or prison guards “pigs”. I opposed abandoning participatory democracy.… I continued to advocate nonviolence’.

The Lynds left ‘The Movement’ to navigate their own way.

Accompaniment

During their time in Chicago, the Lynds considered and rejected several possible options: symbolic direct action as practised by the Berrigan brothers (who famously raided a draft board, burning the draft files outside using homemade napalm); Saul Alinsky’s brand of community organising; and Staughton becoming a steelworker.

The first they rejected, in part, because they felt that ‘symbolic direct actions often do not communicate beyond the small circle of middle-class idealists who engage in them’.

The second, because they found Alinsky’s approach too rooted in a belief that people are motivated solely by self-interest.

And they rejected the third after a young steelworker friend explained: ‘Staughton, you could be [at the steel mill] for twenty years and people would still say to each other: Let’s see what the Professor thinks.’

Instead, the Lynds gravitated towards an approach they called ‘accompaniment’, drawing on a closely-related idea from Liberation Theology.

In their memoir, they summarised this as follows: ‘For us, the idea of accompaniment is that there should be a relationship of equality between the professionally-trained person who has a skill to contribute and the poor or exploited person who can offer the lessons of a different kind of experience.’

In his 2012 book, Accompanying, Lynd also cited physician Paul Farmer’s explanation: ‘I’ll go with you and support you on your journey wherever it leads. I’ll keep you company and share your fate for a while. And by “a while”, I don’t mean a little while. Accompaniment is much more about sticking with a task until it’s deemed completed by the person or people being accompanied, rather than by the [accompanier].’

Guerilla histories and solidarity unionism

For the Lynds, accompaniment involved them both retraining as lawyers and spending 30 years in day-to-day association with rank-and-file workers in Chicago, Illinois, and Youngstown, Ohio.

They also produced a series of ‘guerilla histories’, sharing the insights of ‘persons ordinarily viewed as the mere objects of historical research’. These included Rank and File: Personal Histories by Working-Class Organizers (1973).

At first, Staughton attempted to ‘fly under the radar’ as a labour lawyer, but it was not long before he was ‘outed’ as a radical by the local paper which ran the famous picture from the Assembly of Unrepresented People.

However, this didn’t damage his reputation with everyone.

One worker, recently fired after a wildcat strike, saw the photograph and instantly concluded: ‘That’s the lawyer for me!’

“Because I was pushed from the academic nest, and became a lawyer, I have had an opportunity to come to know rank-and-file workers and death-sentenced prisoners that I never could have had as a university professor”

The fight to resist the shutdown of the steel mills in Youngstown in the late 1970s – during which the national steelworkers’ union either stood aside or sabotaged local efforts – convinced Lynd that ‘only local unions, not any national union or federation of national unions, could be looked to for visionary energy and the seeds of change’.

In addition to their legal work, the Lynds also played an important role in a variety of independent working-class organisations including the Workers’ Solidarity Club of Youngstown and Workers Against Toxic Chemical Hazards (WATCH).

Meeting once a month for 15 years, the Solidarity Club – which always met in a circle – provided a place where workers in the area knew that they could go to get help.

Nonetheless, in 2006, Lynd reflected: ‘I spent 25 years (1970 – 1995), exploring the hypothesis that the central force for social change in [the US] would be the labour movement. My results were negative.’

Fighting supermax prisons

In 1996, the Lynds retired and began joint work with prisoners that would occupy much of the rest of Staughton’s life.

Ohio had decided to build a ‘supermaximum’ prison, the Ohio State Penitentiary (OSP), a half-hour drive from their home.

In 2000, a Human Rights Watch report noted that ‘prisoners in these facilities typically spend their waking and sleeping hours locked in small, sometimes windowless, cells sealed with solid steel doors’, in conditions that one federal judge noted may, if prolonged, ‘press the outer bounds of what most humans can psychologically tolerate.’

The Lynds found that many of the prisoners at OSP had been placed there on questionable, flimsy, or insufficient grounds. Between 2001 and 2008, they corresponded with more than 600 of the prisoners incarcerated at OSP, gathering information that proved to be critical in a federal lawsuit brought on behalf of the prisoners.

The lawsuit won a ‘modicum of due process’ for supermax prisoners throughout the US. The population of the OSP also dropped to less than half its capacity.

The Lynds also spent more than a decade working with five men at OSP who had been sentenced to death as leaders of a prison uprising at Lucasville prison in 1993.

Lynd later described this work as ‘overall the most rewarding… I have ever undertaken as a historian’.

Triggers for change

No fool, Lynd was well aware of the obvious critique of their approach, writing that: ‘A common objection to the idea of accompaniment is that its successes are, at best, small-scale. We are asked: How can one expect such tempests in scattered tea pots, such organizational small potatoes, to result in the deep structural changes in the broader society that are required?’

In part, his answer was that small-scale actions can sometimes act as ‘triggers’ for ‘multiple imitation and widespread change’. This, he noted, had happened with the lunch-counter sit-ins during the civil rights movement, and in the formation of industrial unions in the US in the 1930s.

Lynd also pointed to series of prison hunger strikes in California – in part, inspired by events at OSP – that played a crucial role in effectively abolishing indefinite solitary confinement in the nation’s largest prison system.

One of these strikes lasted around 60 days and involved an incredible 30,000 prisoners, with some 40 fasting for the full period.

A first step

Though they joined the Quakers, the Lynds did not believe in a supernatural deity, and wrote that the resurrection seemed to them ‘unworthy of belief by a rational mind’.

Nonetheless, to a significant extent, their choices about where and how to focus their energies were clearly influenced by Staughton’s commitment to the sentiments expressed in Matthew 25:40: ‘Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.’ This was, he wrote, a passage that ‘came to mean more and more’ to him during his life.

In Accompanying, Lynd wrote that: ‘The practice of accompaniment will not, in itself, take us from where we are to that… “other world”, that the Zapatistas have encouraged us to imagine.… All I am sure about is a first step. That first step… will require many of us on the Left to abandon preoccupation with a novel vocabulary, or a new organization. Instead this book proposes that it should become an expected first step for radical professionals and intellectuals, instead of spending their adulthood in enclaves on the East Coast, West Coast, or Great Lakes, to venture forth into relationships of companionship with ordinary people in places where there may be very few fellow radicals.’

Fortunately, anyone wishing to explore the Lynd’s lives and ideas, will find a rich treasure trove in the books that they have left behind, many of which have been published or re-published by small radical presses over the last 13 years.

PN readers may be especially drawn to the pair’s documentary history of nonviolence in the US from colonial times to the present, Nonviolence in America.