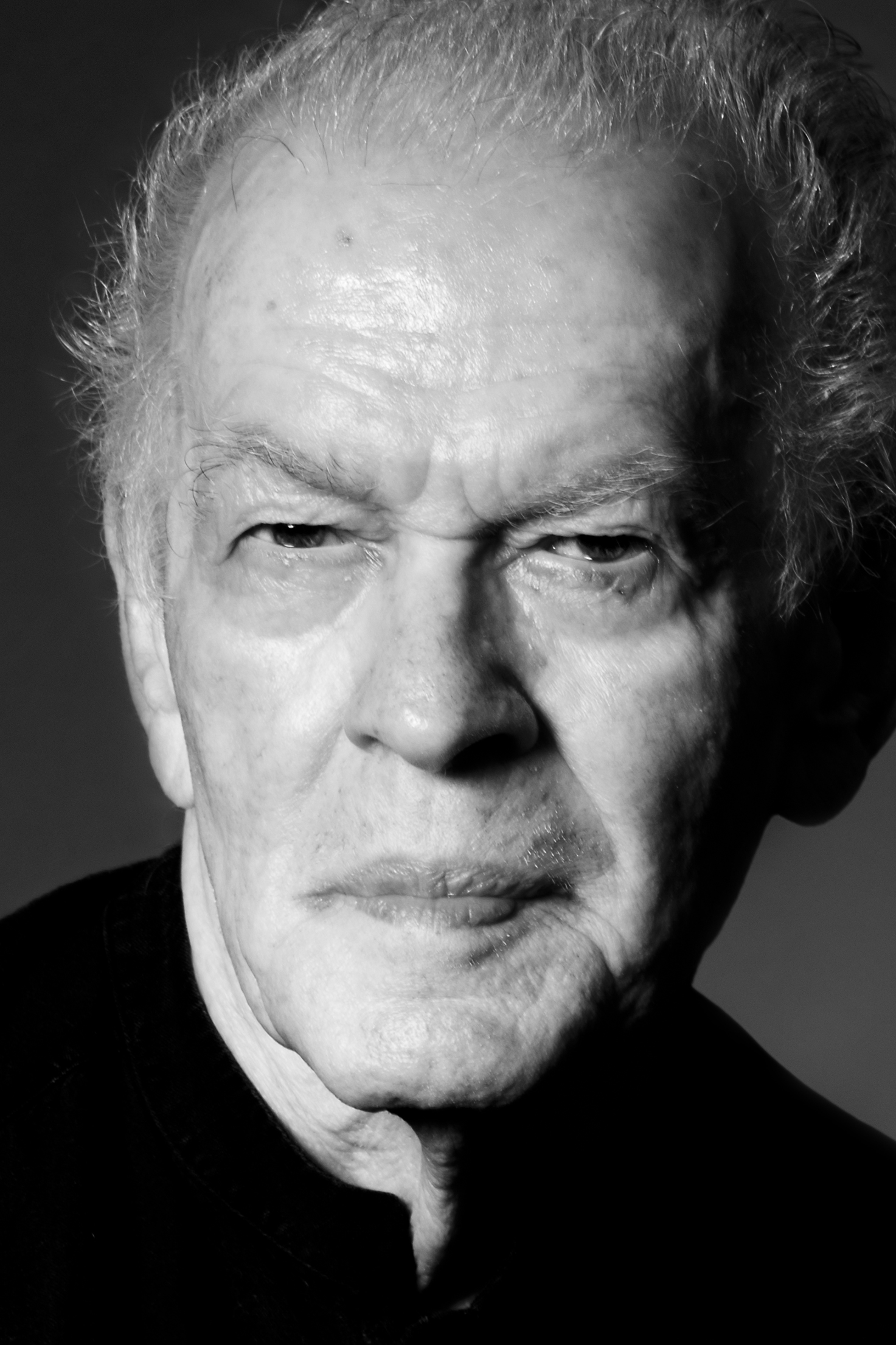

Arguably the best-known advocate of nonviolence working today, through books such as 1993’s 'From Dictatorship to Democracy', Gene Sharp has influenced popular revolutions and revolts across the globe. He was interviewed by Ian Sinclair for PN.

Peace News: When and why did you first get interested in the serious study of nonviolent struggle?

Gene Sharp: Well, the world was in a bit of a mess [after the Second World War], and I began to learn that there was a phenomenon of nonviolence that had been in existence for a long time; that some means of conflict are necessary and people were still trying to use it [nonviolence] in various parts of the world. So this could prove to be very, very important, so I started studying and reading over quite a number of years. It goes way back.

PN: How would you describe your own politics?

GS: I have a chapter on that in the [1980] book Social Power and Political Freedom. And the chapter is ‘Rethinking Politics’. You have to rethink politics, not choose from what’s on the present menu. I cooperate with people with various political perspectives. There’s no one that I find so adequate to simply accept it and embrace it.

PN: You wouldn’t call yourself a pacifist?

GS: Not anymore. That doesn’t mean I’m for violence but, maybe unjustly, or maybe not, pacifists are known for their refusal to use violence. And doing a number of other good things, perhaps.

It goes back to the old PPU [Peace Pledge Union] slogan: “War will cease when men refuse to fight.” But I don’t think you get rid of war that way. I think you have to have a substitute. You have to, unless you just want to make a moral gesture.

I’ve done that [Sharp spent nine months in prison for protesting against conscription during the Korean War]. But moral gestures, to be crude, don’t achieve much, sometimes nothing. Sometimes a little bit.

PN: Underpinning your ideas and arguments is a specific understanding of how power works in society. Could you summarise this for people who may not be familiar with your work?

GS: I will do that but it’s expressed at length in the first volume of the paperback edition of The Politics of Nonviolent Action. I think it’s the first chapter on the nature of political power… Power has sources. It’s not something in a package. And where those sources are there and available to the regime, there can be great power.

I think I identify six or seven sources: a moral authority – they have the right to rule or the right to be our government, for whatever reason; the control of the economy;the control of the civil service; the control of the police; the control of the military; and certain more fuzzy factors, more psychological factors.

If those are available then there’s power. But those sources, people in government positions, they weren’t born with those; they come from somebody else. Those can be traced and they all come from the obedience and cooperation of individuals, or more commonly, institutions and groups of people. They make them available, and in some rare situations their sources are not made available readily, or they’re withdrawn. Massive non-cooperation movements are an example. Then their power is taken away.

That’s why some governments fall apart, like the Soviet Union and Eastern European governments fell apart, because they weren’t able to mobilise those sources.

PN: What are the problems of using violence to overthrow a dictatorship?

GS: It’s foolish. Stupid. If your enemy has massive capacity for violence – and modern governments today have massive capacity for violence – why deliberately choose to fight with your enemy’s best weapons? They are guaranteed to win, almost certainly.

PN: Are there any instances where you have supported violent resistance to occupation or invasion?

GS: I’m often happy that people opposing a regime have won. Libya’s used as an example now, which the Libyans did not do themselves – the French air force, US military capacity and so forth. It wasn’t a struggle by the Libyans, and now it’s not their victory. I was told the number of Libyan casualities and the physical destruction are absolutely horrendous – far, far worse than what’s been going on in Syria, as horrible as that is. You have greater casualties with violence.

It’s a very good chance you’re going to lose and if you get outside help then part of the control afterwards is in the hands of the foreigners for whatever motives. That doesn’t sound very good to me.

PN: What have been the most successful examples of nonviolent revolution in recent history?

GS: There are a whole variety of them. You could look at Poland, for example. It took ten years but they did it. They withstood their own authoritarian regime back in the ’30s. They withstood the Nazi occupation and the Soviet occupation and opposed the Communist government. Eastern Europe – Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania, where we [the Albert Einstein Institution] did consult.

Those countries were already part of the Soviet Union and they got out using these means. We directly consulted with those governments in person. They got out with very few casualties. I think in Lithuania it may have been 14 dead, in Latvia eight and in Estonia nobody was killed.

To me the [resistance to the 1991] hard-line coup in the Soviet Union is another example.

PN: As you will know, with the Arab spring there have been numerous reports of your influence on the various revolutions and revolts.

GS: I don’t know. I get these reports all the time. We had known that there was interest in my writing in Egypt for a few years. We even heard that there was a special headquarters that had been set up in an apartment in Cairo and occasionally we have Egyptians visit us in Boston, Massachusetts. But none of that proves anything in terms of real documentation – how you transfer all the knowledge gained just by reading, talking or listening, to people’s actions.

PN: In How To Start A Revolution you say you are primarily trying to “understand the nature and potential of nonviolent forces of struggle to undermine dictatorships.” Are your arguments and ideas transferable to making radical transformations in industrial democracies like the US and UK?

GS: From Dictatorship to Democracy is only a small piece of my writings. A very small piece. The nature of nonviolent struggle is broader.

My 1973 book, The Politics of Nonviolent Action was never published in the UK. I’m hoping to do it in a large edition to be published here in a couple years. It’s on the nature of the technique: what are its methods, how does it work? That then can be adjusted for application for a variety of broadly democratic purposes – economic objectives, political objectives, anti-colonial movements, extensions of the franchise and so forth.

So you wouldn’t take the model From Dictatorship to Democracy and apply it to social revolution because that’s a different objective. You’d have to have a different analysis. But a nonviolent struggle can be extremely important in the new model for a social revolution.

PN: The most important and influential social movement in the US at the minute seems to be the Occupy protests. What is your assessment of these?

GS: It’s been succeeding and accomplishing what? It’s an expression of people who are very frustrated and quite angry. And for damn good reasons. They think politically they’re not having the impact they had wanted. They see the extreme non-distribution of wealth in the country is getting worse. It’s coming out even in the Republican debates with the candidates there.

So people who’ve been in the middle class their whole lives are now becoming quite poor. And I don’t know what political consequences there are going to be over this but all that is happening.

The Occupy movement expresses some of that frustration. It has spread not only within the United States but also in other countries. Because people think there’s something they can do. But they think that by expressing themselves, they think that’s going to change things. And to be honest it won’t. It’s too little. Not enough. It is only symbolism.

You don’t get great economic and political changes by symbolism only, which any radical would agree with. Now whether they will do other thinking, they are going beyond this – there are some signs that some of them are. Whether it’s going to be adequate, I have my doubts. If they do this thinking they are going to win, and they don’t, they may collapse and think: “We’re as helpless as we thought we were and so won’t do anything.” Or they’ll go over to violence which will bring down greater repression, predictably. It won’t change the situation.

PN: You have been involved in activism and academic writing and work for a long time. What keeps you going? Do you have moments of doubt?

GS: Not really, no. Maybe I’m kind of a stubborn person. That always helps. To see on the one hand the great need for the application of nonviolent struggle, to see the great impact when it is applied wisely, which is not always the case.

Sometimes you get contact and letters from people you had never heard of, about what this has meant for them, sometimes individuals see the movement developing.

And sometimes you see the regime has come down. The victors have won. That’s encouraging.

But we can still learn to do this more skilfully, more effectively. Sometimes we know a lot, but people are unaware of what we do know. Sometimes we may not know what we need to know.

My ignorance is vast.

People come and ask me what they should do, and I say: “I’m not going to tell you! I don’t do that. Here’s what you need to learn and understand in order to do this yourselves.” That’s why our guide is called Self-Liberation.

You may have seen this, it’s on our website. It’s kind of deceptive but not on purpose. People would come to us and finally we figured out what they need to plan a strategy, they need three things. They have to know their own situation in depth, far better than we would know it – they need to know it better.

They need to know nonviolent struggle in depth. Not the superficial impressions that people claim they know – they don’t. So there’s a condensed version of what they need to read, it’s only 900 pages. And that’s condensed.

And then they need to learn how to think strategically; how to act facing opposition so you can actually accomplish something. Strategy being probably more important in nonviolent struggle than it is in military conflict. If they learn all that, then there’s a chance they can plan their own struggle.

PN: But surely most people in Egypt and other places where they have used your ideas and arguments have not read all your writings?

GS: No, but the masses of people didn’t formulate the strategy. That is for getting people competent enough to plan a strategy. Then there are many people who can be very important and very effective in conducting a struggle – they don’t have to read all that. But somebody needs to – as many as possible – need to have that know-how. This is people learning how to do this. This is new.

They don’t need a Gandhi.

What if this existed in 1930, all this knowledge and knowhow? Before Hitler came to power? If people who struggled against Hitler had greater knowledge of how to conduct struggle effectively to prevent him ever succeeding in becoming chancellor in the first place?

When Hitler came into the government the Nazis were very frightened of a general strike. A nonviolent method. They were very frightened of that. If only the opposition really knew how to conduct this kind of struggle effectively, the world would have been very different. But it didn’t happen.

You ask me: “Why don’t I call myself a pacifist?” I don’t favour violence but I think the old assumption “you’re either for war or you’re a pacifist” is wrong.

There’s a third position, which I think was Gandhi’s position. I’m working to develop nonviolent struggle as a viable alternative. Only if you have a viable alternative can you have a chance of getting it used and being effective. And that is not a case of refusing to use violence, that’s a case of using nonviolent struggle competently. That needs a new name. I’m not sure what that name would be.