In Shiraz, on Day Four, while we were waiting for our minibus to show up to take us to lunch, a man walked by carrying an old rifle. I’m not an expert on guns, but it looked really old, perhaps even a First World War-type Lee-Enfield. (Now that I’m home, I find that these are still used all round the world.) The man carrying the rifle was dressed in civilian clothes, and walked along the road casually, seemingly without a care. Probably a hunter, we guessed.

The striking thing about the incident was that after four days of roaming the country (and passing through three airports), he was the first armed person I’d seen in Iran. During the whole ten days, seeing several policemen and soldiers, I only saw two other people carrying guns: a guard outside a bank, and a police officer outside the Tourist Police headquarters.

In London, it’s not uncommon to see armed police. We saw two standing guard with submachine guns in a London train station just a few days after returning. Even the unarmed police in Hastings wear stab jackets and handcuffs and a baton and other equipment, and they look paramilitary. Police we saw in Iran wore hi-visibility tabards saying ‘Police’, and sometimes carried a truncheon. It was a startling difference.

This doesn’t mean the police in Iran were to be trifled with, or that there isn’t a massive security system there. It’s just that, on the street, guns were not visible in the four cities we visited.

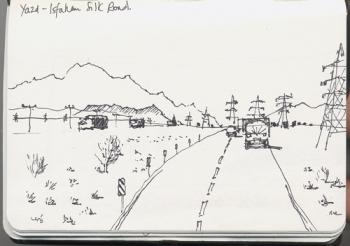

In the ancient city of Yazd, our group saw a traffic accident. One pickup truck knocked into another at a crossroads. Headlight glass spilled in the middle of the road. A policeman appeared from nowhere (unarmed, of course) and calmly directed the drivers to park in different locations and await further instructions, which they did. There was no shouting, no gesticulating, no honking of horns by other inconvenienced and impatient drivers. Law and order, Yazd-style.

The revolution

In the Holy Defence Museum in Tehran, we saw footage and photographs of the 1978-79 revolution, whose anniversary was celebrated while we were in Iran. I don’t think it would be right to call it a nonviolent revolution. The final collapse of the regime involved several days of street fighting. I do think it is fair to call it a largely unarmed revolution. At the heart of the revolution were the strikes by workers and merchants that undermined the dictatorship, and the unarmed mass uprising of hundreds of thousands of ordinary women and men who were willing to go out on the streets and risk their lives to overthrow the shah, while calling on soldiers and the police to abandon him. After protesters were shot down, more and more people poured into the streets; as hundreds died, the numbers of demonstrators grew, until over 10% of the population of the entire country took part in the final demonstrations. I find this courage incredibly moving.

The most powerful military force in the region (apart from Israel), perhaps the most feared secret police in the world (apart from the CIA), a massive, brutal apparatus of repression pretty much disintegrated in the face of an enraged, unarmed people.

When the military put censors into two major newspapers in Tehran in October 1978, the journalists and others simply refused to work, and other newspapers went on strike in sympathy.

When, in January, the military tried to force state television to show pro-shah material, they were told by management that if the programme was shown, TV staff would assume the network was in the hands of the military and would not show up for work.

Electrical workers in the major cities cut the power every evening in December for two hours in order to disrupt the state television news, and to help demonstrators who were violating the 8pm curfew.

Military technicians were sent in to take control of the oil industry (to replace striking workers) but were overcome by the technical challenges and shut down operations. Oil workers were forced to go back to work at gunpoint, then went on strike again as soon as possible, a pattern repeated by the airlines, telephone services, banks and customs officials.

The military could only focus their coercive power in a few places at any one time. As soon as the pressure slackened off, people re-started go-slows and strikes. (See Charles Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, Harvard University Press 2004, pp112-114)

These are very different facets of the Iranian experience. Nevertheless, it is true that the revolution was largely made by mass defiance, mass noncooperation, by militant nonviolence on a massive scale. The regime is well aware of the power of the people, and the need to maintain legitimacy in the eyes of the majority.

The 65% turnout and the wide spread of candidates participating in parliamentary elections last year demonstrated that the political system is still legitimate in the eyes of most Iranians, as Seyed Mohammad Marandi of Tehran University pointed out a year ago. (Marandi noted that the turnout was 38% in the equivalent 2010 US congressional elections.) The absence of guns at every corner is another demonstration of the perceived legitimacy of the system, and also part of how the system retains its legitimacy.