On 19 March 2003, the United States and Great Britain embarked on the invasion and occupation of Iraq. Widely considered one of greatest foreign policy disasters of modern times, the war was only the latest in a series of western military interventions in the country over the course of the last century. A decade on from the invasion, the war is being revisited in British public culture across newspaper articles, television programmes, debates, interviews with politicians and other events. Many of these rehash the issues and controversies that have raged over the course of the last 10 years, addressing issues of accountability, responsibility and whether the war was in some sense justified or ‘worth it’.

Looking beyond these debates, how might it be possible to think differently about the war, to gain alternative perspectives beyond those of politicians and commentators? What did the war actually mean to people within and beyond Iraq?

These kinds of questions have guided my research over the last two years into how artists and art institutions in the UK responded to the war. In the course of this research I have looked at over sixty art works, exhibitions and events, spanning a wide range of artists and practices ranging from fine art, to abstract contemporary art, to street art and activism. By looking at these responses, I have asked whether it might be possible to uncover a different and possibly more revealing picture of the war, a picture that might offer ways of rethinking questions of militarism, resistance and peace more broadly.

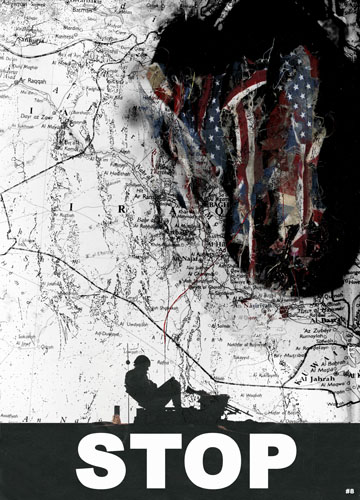

Immediately striking is of course the upsurge of artistic and creative protest in advance of the invasion itself, with huge anti-war protests that took place in London and other major cities around the world. While established British artists and designers such as David Gentleman, Peter Kennard and Cat Phillipps (working as kennardphillipps) and Banksy supported the anti-war movement with memorable images, well-known pop artists like Gerald Laing and Richard Hamilton appropriated and redefined the visual language of the war, affirming opposition to it. In these ways, artists not only reflected but also contributed to public perceptions more widely.

Iraqi artists

Far less exposed in the media has been the work British-based of Iraqi artists and curators such as Rashad Selim, Dia Azzawi, Yousif Naser, Adalet Garmiany, Satta Hashem, Suad al-Attar and Maysaloun Faraj who also responded to the invasion with a series of art works and exhibitions.

In contrast to the directly political approaches of many British artists, many of these works and exhibitions by artists with ties to Iraq have reflected the ways in which modernist influences have been appropriated and adapted in Iraqi art. While less obviously political, their works have explored the destruction of the country, the loss of heritage, the trauma of violence on bodies and landscapes and feelings of estrangement and distance.

Indeed, not all members of the Iraqi community in Britain — artists included — were necessarily opposed to the war. For many who left as a direct result of oppression by Saddam Hussein’s regime, the invasion held some hope that it might in some way lead to a better future for Iraq. The combination of horror at the violence of war and yet a degree of ambivalence about its implications has been reflected in Yousif Naser’s series of Black Rain paintings, which he began before the invasion and has continued to paint until the present. In these mixed-media canvases, which are influenced by German expressionism — itself a reaction to the extremes of war — British newspapers are often painted over in with deep, black shadowy figures and oppressive dark shapes.

While the work of Naser and Suad al-Attar seeks to deal with inner as well as outer violence and devastation, Dia Azzawi has created works that celebrate and commemorate Baghdad as an ancient, beloved city, Rashad Selim has highlighted how Iraq and Iraqi culture have always been part of broader cultural relationships and exchanges, and Maysaloun Faraj has affirmed family, place and landscape in bright, engaging canvases. In each case, as with Satta Hashem’s drawings and paintings, in which everyday events are blended with scenes and symbols from Mesopotamian cultures as well as contemporary politics, artists have presented a far broader picture of Iraqi life, history and place than has been available in the media more generally.

The outflow of art and artists from Iraq continued with the war, with Hana Malallah, one of the leading contemporary artists still working in Iraq, forced to leave the country by growing sectarian violence and threats towards academics and artists. Having developed as an artist in the context of war and sanctions within Iraq, Malallah’s complex multi-media works, which often use burning and tearing as well as painting and craft techniques, express both an experience of war and a sense of loss at the destruction of her country and the loss of its heritage. Her work, like that of other Iraqi artists, implicitly poses the question of how it might be possible to connect with and support artists and communities remaining in Iraq and whether it might one day be possible to return.

Resistance is not just about overt protest, but also the affirmation of things that matter

So what might be drawn from 10 years of art made in response to the war? While leading British contemporary artists like Steve McQueen (who proposed a series of stamps featuring photos of British soldiers killed in Iraq), Mark Wallinger (who recreated Brian Haw’s anti-war protest inside Tate Britain after it was largely cleared from Parliament Square) and Jeremy Deller (who installed a car destroyed in a suicide bombing in Baghdad in the atrium of the Imperial War Museum) have each made high-profile statements, achieving widespread recognition and praise, their works have struggled to connect with or involve Iraq and Iraqi people. Similarly, though art made by artists embedded with the military or by soldiers themselves can also be interesting for what it tells us about the trauma and anxiety of war, it can say little about the experience of Iraq and Iraqis themselves.

By recognising and affirming the work of Iraqi as well as British artists, it is possible to gain a much deeper and richer sense of how the war has been expressed and resisted through art. Here resistance is not just about overt protest, but also the affirmation of things that matter, of connections and endurance, as well as giving material form to the pain of war. Having a broader and more inclusive view of how art and artists have responded to the war also gives a better sense of some common themes that are shared by people across geopolitical divides: a sense of place, of home, of connections with the landscape, with city and country. In bringing war home, art can express resistance but perhaps also affirm those things in common that ought to provide a foundation for peace.