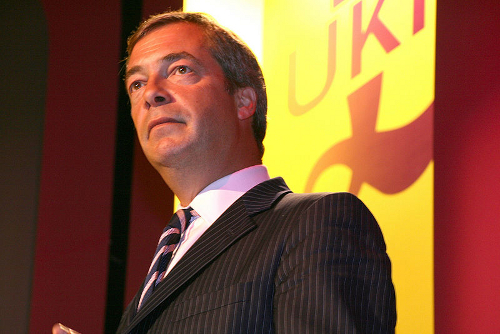

.jpg) There is something hopeful about the rise of UKIP (UK Independence Party). Yes, it is a racist far-right party; yes, the mainstream parties have responded to its increasing strength by becoming more repressive and racist; and yes, it may win several seats in the general election in May 2015 – all frightening developments.

There is something hopeful about the rise of UKIP (UK Independence Party). Yes, it is a racist far-right party; yes, the mainstream parties have responded to its increasing strength by becoming more repressive and racist; and yes, it may win several seats in the general election in May 2015 – all frightening developments.

On the other hand, UKIP is part of a global anti-establishment phenomenon which in Europe is represented not only by far-right parties like Golden Dawn in Greece or the Northern League in Italy, but also by radical left groupings like Syriza in Greece (with much more power than Golden Dawn), Five Star in Italy (with much more support than the Northern League), and Podemos in Spain (where there is no significant far-right party).

Syriza, or the Coalition of the Radical Left, is currently the second-largest party in parliament, and the most popular party in Greece, and may well win parliamentary elections in 2016.

Five Star in Italy, which is an unclassifiable anti-war party of participatory democracy, gained 21% of the vote in the European elections in May 2014, and 25% of the vote in the general election in February 2013.

Podemos (‘We can’) in Spain, was only founded in January 2014 and it still gained 8% of the vote in the May 2015 European elections. One recent poll found that it was the strongest party in the country with 28% support.

It’s complicated

In other words, the rise of UKIP is part of a growing disillusionment with mainstream politics that is affecting all the industrial democracies. Analysis of UKIP supporters in 2012 by Matthew Goodwin and Jocelyn Evans found that, in relation to democracy, UKIP supporters were very dissatisfied (39.8%) or fairly dissatisfied (34.3%) with the way democracy works in Britain.

Earlier, polling in December 2012 by lord Ashcroft’s agency found that potential UKIP voters were not attracted by the party’s policies as such; ‘Analysis of our poll found the biggest predictor of whether a voter will consider UKIP is that they agree the party is “on the side of people like me”.’

The profile of the party has changed quite a bit in the recent surge.

Countering UKIP will mean reaching out in many ways to the older, white population that supports the party, and convincing people that their interests are served not by repressing people on benefits, immigrants and Muslims, but by more democracy.

The 2012 study by Goodwin and Evans found that UKIP supporters were overwhelmingly men (72%), older (66% over 56), and middle-class (63%). YouGov polls of UKIP supporters in October 2014 suggested that, in all areas, this had evened out a bit, with men a smaller majority at 57%; the age profile having lowered so that only 41% were over 60, and only 43% were middle-class (compared to 57% in the general population).

Matthew Goodwin and Robert Ford have pointed out in the Guardian that UKIP has won more and more working-class support: ‘These voters are on the wrong side of social change, are struggling on stagnant incomes, feel threatened by the way their communities and country are changing, and are furious at an established politics that appears not to understand or even care about their concerns.’

Goodwin and Ford’s research has found that for these economically-insecure UKIP supporters, the key issues are not economic but rooted in identity and values: ‘These voters have been left behind not just by wider trends, but the rise to dominance of a university-educated, professional middle-class elite whose priorities and outlook [and language] now define the mainstream.’

A strategy

Perhaps we can learn something from the US here. The state of Oregon is 81% white and predominantly working-class/working poor, with a tendency towards conservative politics and religious fundamentalism. The Rural Organising Project (featured in Chris Crass’s book, Towards Collective Liberation) organises white, increasingly-impoverished rural people as allies for racial, economic and gender justice.

ROP organises Living Room Conversations, literally in people’s living rooms, with neighbours, family and friends, to analyse the anti-immigrant movement in Oregon, debunk anti-immigrant myths, and facilitate discussions about what is going on in the local community. People who are willing are then signed up to the ROP Immigrant Fairness Network and their local Rapid Response Team.

This face-to-face work is part of what is needed now in Britain.

Countering UKIP will mean reaching out in many ways to the older, white population that supports the party, and convincing people that their interests and values – the interests and values tof ‘ordinary people’ – are served not by repressing people on benefits, immigrants and Muslims, but by more democracy, more people’s control of our economy, and less power for corporations and the state.

Syriza and Podemos come out of powerful social movements. That’s why they are forces to be reckoned with. Our most important goal must be to build powerful extra-parliamentary social movements that can help move society towards radical democracy and economic and environmental justice. In that process, we can win people away from fear-based politics and towards a politics of nonviolence and collective liberation.