Tom Morton-Smith’s newly-commissioned play for the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) – the story of a great figure brought low by a fatal flaw – has something of the classical tragedy about it.

Tom Morton-Smith’s newly-commissioned play for the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) – the story of a great figure brought low by a fatal flaw – has something of the classical tragedy about it.

Watching a previous dramatisation of the ‘father of the atomic bomb’ (the BBC’s seven-part series Oppenheimer, first broadcast in 1980), some reviewers could believe that the defect lay in physicist J Robert Oppenheimer’s early communist sympathies, his adultery and his post-war political conflicts.

Here, concentrating on the period 1936-45, it becomes clear that it is personal and intellectual ambition that leads to the fall, when physicists had ‘known sin’. The playscript book includes an epigraph from Kurt Vonnegut: ‘Just because some of us can read and write and do a little math, that doesn’t mean we deserve to conquer the Universe’. Oppie’s ambition seemingly estranged him from his wife Kitty and former lover Jean Tatlock, and created an ogre that continues to stand over the world.

Morton-Smith draws on both the BBC series and the 2005 biography American Prometheus, adding vibrant physical theatre and imaginative asides. The staging is simple except for the Trinity test bomb that hangs over the stage in the middle of act two, while the ‘Little Boy’ bomb is represented, literally, by a child.

The long first half plays with ideas, balancing the political, the personal and the physics, and quickly sketches a potentially bewildering ensemble of characters. The second act wrings out greater emotional intensity, culminating in the horror of Hiroshima, conveyed effectively in words, and by a man in front of a blackboard explaining how to calculate the height of an airburst from the shape of the ‘human shadows’ burned into stone by the blast.

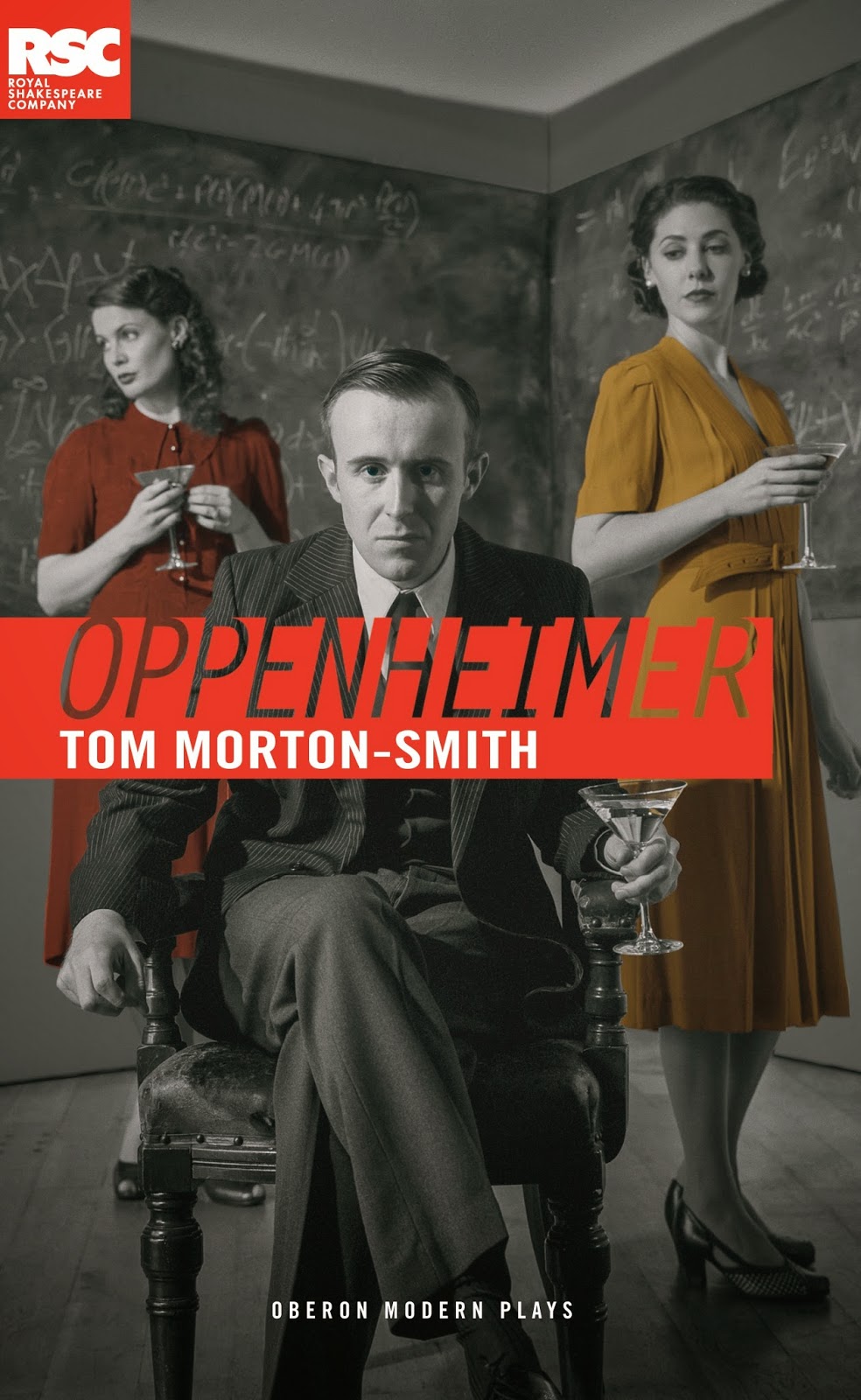

Photo: Keith Pattison

Oppenheimer (played by John Heffernan) maybe has ‘nullified war’, but concludes ‘instead I feel like I’ve left a loaded gun in a playground.’ The play also touches on paths not taken: not building the bomb; giving it to the nascent UN; harmlessly demonstrating it to the Japanese. The possibility of Japanese surrender, and the withholding of intelligence about Germany’s lack of nuclear capacity from the physicists are among the few aspects not mentioned – the focus of the play being the scientists and their loved ones rather than the generals. A topical theme of state surveillance and paranoia – to which Oppenheimer sacrifices his brother Frank – is also played out.

Moral questions are met by Oppenheimer’s awkward charm and assumed military rank, while the title character, steep’d so far in blood, is positioned between Edward Teller, already looking forward to his H-bomb, on the one side, and by the caution of Robert R Wilson and a emotive plea for human modesty from Frank on the other.

The five-star review from the Telegraph indicates that this may not be a polemic leaving the audience demanding unilateral disarmament, but it is nonetheless an excellent introduction to the birth of the bomb.