The Lucas Aerospace plan was developed in the mid-1970s by workers who wanted to move the aircraft manufacturer away from military production towards socially-useful production, in order to make their jobs more secure and more productive.

Lucas Aerospace had 18,000 workers spread out over Britain in 17 different factories, making collective action a real challenge.

The workforce was also divided into 13 different trade unions, adding to the difficulty of working together.

Despite this, the workforce created a Shop Stewards’ Combine Committee that brought together white-collar and blue-collar workers across all the different sites and across all the different unions.

It was the Combine Committee that spent a whole year developing a strategic plan for diversifying away from aerospace.

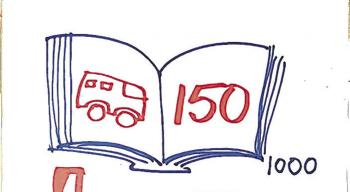

The Combine Committee sent questionnaires to each plant to get a picture of existing production, and asking for suggestions for alternative products. Some outside experts also contributed ideas. The final plan set out 150 possible new products that Lucas Aerospace was capable of manufacturing with its existing machinery and skill base.

The plan was backed up with 1,000 pages of technical and economic analysis.

The Combine Committee then selected 12 products to present to management, including an innovative road-rail vehicle, designed in collaboration with North East London Polytechnic.

The Lucas Aerospace plan met with stiff resistance from the management. It was also unpopular with the trade union leaderships of the day, who were uncomfortable with a Combine Committee that crossed union boundaries and unified the entire workforce, even bringing in technicians and researchers who often tended to identify with management rather than their fellow workers.

The Combine Committee and the Plan pointed the way to a more participatory, radical and grassroots-oriented labour movement, threatening both managers and senior union officials.

There were special features of Lucas Aerospace as a company that made it easier to develop a plan. The workforce was highly-skilled.

Secondly, Lucas Aerospace factories were geared up for very short production runs. These two factors made the firm very adaptable and the workforce used to innovation.

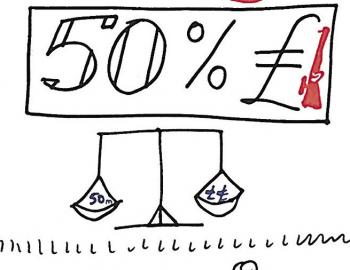

Half of the firm’s income came from military production — almost all for the British government. Also, the company received in government subsidies almost exactly the £50m it paid in taxes.

The dependence of the company on government spending and subsidies should have made it easy to get the Lucas Plan accepted by the management as part of a long-term compulsory planning agreement of the sort championed by minister Tony Benn at the time. This would have been a triangular production agreement between the management, the workforce and the government.

Investment not austerity

As US Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz has pointed out: ‘There has never been any successful austerity programme in any large country.’ Austerity packages ‘depress demand and weaken economic growth’.

What’s needed, according to Stiglitz, is investment in growth, in productive sectors such as education, health, infrastructure and technology, which he calls ‘high-powered investments’.

If there are going to be cuts, Stiglitz argues they should be in areas with low returns on investment, such as wars and ‘weapons that don’t work against enemies that don’t exist’.

Jobs not Trident

The government has committed itself to replacing the Trident nuclear missile submarine system, Britain’s only nuclear weapon, with a similar set of submarines and ballistic missiles. This will cost £205bn over the lifetime of the submarines, according to the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

CND says if Trident were scrapped and its replacement cancelled, this could pay for: 100,000 wind turbines; the employment of 150,000 nurses; 1.5 million new homes; 2,000 new primary schools; the insulation of 15 million homes; free public transportation for generations; or clean drinking water for everyone on the planet.

Green energy not Trident

The shipyard in Barrow that builds nuclear submarines has the skills needed for wave, tidal and offshore wind power.

According to a CND report (Trident, Jobs and the UK Economy, published in October 2010): ‘If we invest the money saved by cancelling Trident, we could make the UK a world leader in wave and tidal power technology and create hundreds of thousands of new jobs in Britain, more than compensating for the jobs lost by cancelling Trident replacement.’

A Just Transition

In 2008, the TUC called for a ‘Just Transition’ to a low carbon economy: ‘Just Transition measures are needed to ensure that job loss as a result of environmental transition is minimised and that change within sectors does not occur at the expense of decent work and decent terms and conditions.

‘A Just Transition strategy is also required to ensure that environmental initiatives not necessarily related to employment - for example, green taxes - do not impact on lower income groups.

‘Substantial evidence exists that environmental transition happens fastest and most efficiently when workers are involved.’

Conversion & democracy

US scholar Seymour Melman spent a lifetime contesting the military-industrial complex. He wrote: ‘A vigorous nationwide effort for demilitarization and economic conversion would create a net increase in civilian jobs providing that cuts in military expenditures were transferred to the civilian economy.

‘Economic conversion has three essential components. It must be ordered by law, planned, and undertaken locally in each defence factory, laboratory, and military base.’

Melman supported the idea that at every significant military facility, an Alternative Use Committee should be set up, of not less than eight members, with equal representation of the facility’s management and workers. Melman believed that grassroots democracy in the workplace would be an essential part of any effective conversion programme.

More information

- Mike Cooley was a trade unionist and designer at Lucas Aerospace and involved in drawing up the Lucas Plan. He later did innovative work at the Greater London Enterprise Board. His book Architect or Bee? The human/technology relationship, first published in 1980, has just been republished by Spokesman, 194pp; £10.99.

- Online, you can see a 1978 documentary, as well as a recording of a June 2016 meeting (about the Plan and Architect or Bee?). Search for ‘Lucas Plan’ on YouTube.

- There is a 2014 research paper on the Lucas Plan online: www.steps-centre.org