Has the election of Donald Trump as president of the US got you down? Are there days you just don’t believe any more that we can win, that we can change big important things?

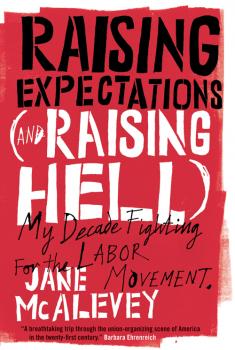

Jane McAlevey’s Raising Expectations (and Raising Hell) is the perfect antidote to Trump-era pessimism and despondency. I’m going to buy a bunch of copies for people I know, and I think you should too.

There are books out there filled with inspiring thoughts and dreams. This book is packed with dreams turned into reality, with big wins won in the face of impossible odds. Raising Expectations (and Raising Hell) fizzes with energy and determination and success.

In a talk in London recently, US trade union organiser Jane McAlevey made it clear she is only interested in winning – and in winning big. Raising Expectations (and Raising Hell) is the story of some of her wins.

Slow down to speed up

After student activism, training in community organising, solidarity work in Central America, environmental justice work, three years leading trainings at the legendary Highlander Centre, and a spell in a liberal foundation making grants, McAlevey joined the labour movement in 1998. The organising department of the US national trade union federation, the AFL-CIO, sent her out to Stamford, Connecticut, as part of an experimental programme. There were almost no unions in the city and its surrounding county, Fairfield, and the ‘Stamford Organising Project’ was supposed to build unions from almost nothing – fast.

Resisting the pressure to get out there doing something straight away, McAlevey instead launched a two-month ‘power structure analysis’ (PSA) of Fairfield county: ‘You identify the real power players in a given community or area, determine what the basis of their power is, and find out who their natural allies and opponents are. Based on that knowledge, you formulate a plan for enhancing the power of your allies and neutralising that of your opponents.’

McAlevey’s string of successes in the years since 1998 has been based on her insistence on always doing this preparation before taking action. However, her idea of a PSA is not a backroom exercise contracted out to university-educated researchers. That’s just phase one. Phase two is ‘an equally exhaustive pooling of the collective knowledge of our members, carried out by organisers and worker leaders.’

McAlevey explains that this kind of PSA was meant to be ‘not just a tool for developing strategy for building power, but a power-building process in itself, as workers began to realise they had resources they never even knew about – personal relationships, social networks, and knowledge of their community – which could be mobilised on their behalf.’

McAlevey explains that this kind of PSA was meant to be ‘not just a tool for developing strategy for building power, but a power-building process in itself, as workers began to realise they had resources they never even knew about – personal relationships, social networks, and knowledge of their community – which could be mobilised on their behalf.’

This meant starting phase two with a meeting of all the local members of the four unions backing the Stamford Organising Project: a few HERE members from a hotel, some UFCW grocery store workers, municipal workers recently organised by the UAW, and staff from the Honey Hills nursing home just organised by SEIU District 1199NE. McAlevey writes: ‘The idea of starting this unstructured conversation among workers from different unions doing different kinds of work was even farther out than the idea of the PSA itself, but the board approved.’

She goes on: ‘We had secretaries who kept the calendars for the city’s top officials and knew all about who met with whom in Stamford’s corridors of power. We had people from the assessor’s office who knew exactly which corporate land values were being assessed low in return for campaign contributions. The nursing home workers offered sharp insights into which churches mattered in local politics, which pastors mattered, and the relationships between them... The mix of class and race in that first meeting created some amazing dynamics that would continue throughout my time in Connecticut. Government workers, white collar and mostly white-skinned, joined nursing home workers who were generally African-American, Jamaican or Haitian.’

Throughout the book, we see McAlevey fighting racism and racial separation in the US labour movement, and the immediate, practical advantages for workers of building solidarity and connection across racial and other divisions. She recalls that in Stamford, ‘We had huge, unwieldly meetings with translations in Creole, Spanish, and English. Workers would say there was no place else in Connecticut where people bothered to translate for them. And we paid for child care at all of our meetings – good child care.... We found that if you make child care available, mothers will turn out in droves.’

Borrowing power

The unions in Stamford had very little power in Fairfield county; they needed to ‘borrow’ some power from the only possible powerful allies, the churches.

After several weeks ‘charting’ the workers in unions connected to the Organising Project, McAlevey and her staff found rank-and-file members who attended powerful black churches. She ran trainings for union members by church, preparing them to have meetings with their ministers to ask for help in getting good pay and conditions from their employers. Influential black ministers began putting pressure on the white mayor and other ambitious politicians in the county.

One of the project unions began organising nursing homes owned by a union-busting national chain, Vencor. Vencor fired a worker leader, Mary Cadlet, a deeply religious African-American certified nursing assistant. The day after her firing, McAlevey called a rally outside the nursing home: ‘A whole entourage of ministers showed up, along with state senator majority leader Jepsen and a number of other politicians.’ Two weeks later, the workers in the nursing home voted by a decisive margin to form a union. The Organising Project won two ‘first contracts’ in Vencor homes. (A first contract is an agreement between management and the union on pay and conditions.) ‘A little more than one year in, the Organising Project had five organizing wins and first first contracts.’

Things ramped up as the Organising Project addressed the housing crisis in the city, which the PSA had identified as the big local issue. The public housing authority announced it would ‘improve’ (demolish) the Oak Park housing estate, which would drive subsidised housing out of Stamford.

The unions organised the residents (many of them newly-organised union members), and hundreds took over and derailed a crucial housing authority meeting on the estate. The Organising Project brought in a load of university students to organise all the public housing complexes in the city, and target protests on the mayor.

The results of McAlevey’s efforts: ‘The Stamford Organising Project had helped 4,500 workers successfully form unions and win first contracts that set new standards in their industries and the market.

‘Beyond that, the Stamford Project had saved four public housing projects from demolition and then won $15 million for improvements to that housing. We’d also won the nation’s strongest “one-for-one” replacement ordinance, protecting thousands more units of affordable public housing, plus an “inclusionary zoning policy” from which the workers in Stamford will benefit for years to come. Finally, the Project had actually shifted political power in the city, with two new city council members and one school board member elected in union-led campaigns.’

This was in contrast to the three other experimental AFL-CIO organising projects, none of which managed to organise a single worker, despite receiving significantly more money than Stamford.

Instead of building on the success of the Stamford experiment, the AFL-CIO ignored the project and disbanded its staff, the first of many times that McAlevey’s work has been sabotaged by trade union leaderships, which is the depressing part of this book.

How to win

What were the secret ingredients in Stamford? One of them was what McAlevey calls the ‘whole worker’ approach. In her view, the job of a union is to help workers to build collective working-class power so they can make their lives better, whether that is in the workplace or outside in ‘the community’. The project was successful because of ‘the successful synergy between labour and community organising’: ‘These workers were changing their entire lives, not just their work lives, and they were doing it from the foundation of their union.... They were fundamentally building worker power, and it was an experience of community, class, race, faith, and personal liberation.’

Another key factor was McAlevey’s reliance on old-fashioned one-to-one, face-to-face organising, assessing workers, recruiting members and identifying ‘organic leaders’ in each department and on each shift.

Here I have just summarised the first chapter in McAlevey’s book. I haven’t mentioned her jaw-dropping wins in Kansas City, in Washington, in Fresno, and in Las Vegas (most of the book is about this extraordinary multi-hospital, multi-corporation campaign). The organising that McAlevey describes is just staggering in terms of the worker militancy, the ultrademocracy, the determined strategy-making, the rigorous attention to detail, the excitement, the boldness, the pinpoint precise theory and the sheer hard work involved in enabling thousands of workers to win life-changing victories for themselves.

This book is a shot in the arm and a challenge to everyone struggling for peace and justice.