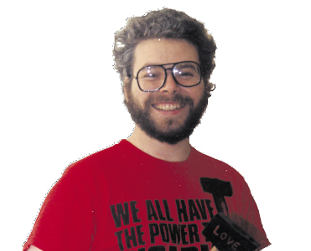

We talked about class with Catholic peace activist Chris Cole during the DSEI week of action. He had been arrested a few days earlier (in his first lock-on) while blockading the set-up of the arms fair with other Christian peace activists. Chris has been involved in nonviolent direct action for almost 30 years. We met him at the British Library where he was carrying out research as part of his work as co-ordinator of Drone Wars UK. Among other roles in the peace movement, he was once director of the Fellowship of Reconciliation.

My dad would say: ‘We’re working-class, we vote Labour.’ For him, I think it was economics, income, but it was also the type of job. He was a factory worker. Until I was 13, my dad worked for Pascall’s, a sweet manufacturer. They boiled up sugar, poured it into various moulds to make boiled sweets. He used to come home often with burns on his hands. My mum was a factory worker too, she worked in the rag trade, in sweat shops, then didn’t work when we were small. Later, she got a job as a dinner lady.

It’s almost like a taboo subject now, isn’t it? Nobody talks about class. The only people who talk about class tend to be Marxists. I don’t know where I stand. I guess I’m middle-class from a working-class background.

Things overlap

I grew up in Balham, in south London. My parents rented a house, they shared it with my mum’s sister and her husband. The landlord of the house died, and my mum and dad and my aunt and uncle eventually managed to get a mortgage from the council and bought the house together. My aunt worked in a warehouse, Freemans, putting together catalogue orders and dispatching them. My uncle was a security guard a lot of the time.

“Somebody whispered into your ear the secret of life. We never got that.”

I have one brother and one sister, I’m the youngest. My three cousins also lived in the house so there were six of us children in the house. It was fine but there were tensions just living together. For instance, we only had one bathroom, so that often caused tension. I didn’t think about it at the time, but three of the children were disabled with learning disabilities, because we have this genetic condition in our family.

There were pockets of very poor families in the borough but I wouldn’t say our area was very poor, there were certainly some home owners. There were derelict houses at the end of the street that had been bombed in the war and we used to play in those when I was very little.

I went to a Catholic school, we grew up as very practising Catholics. My mum was Irish, there was an Irish community around but I did sense it was kind of frowned upon. All of these things overlap. There was class prejudice and prejudice about our Irish background.

One of my friends at primary school, his father worked at The Times, so they had quite a big house about half a mile away from where we lived. I always remember being amazed going to his house and they had all this space to themselves. It’s funny because we have that now. When our kids were small, their friends would come around to our house and they saw our house as being huge.

Formative times

I did well at O-levels. There are two ways of looking at what happened next. One is that I did the wrong subjects at A-level, I took very science-based subjects and didn’t do very well. I also very much discovered girls and alcohol and social life, and just didn’t study hard enough. My dad was very, very upset and disappointed that I didn’t go to university. My daughter Beth is going to university next week, she is the first one on my side of the family to go. But I did later get accepted on an MA course when I was 35 so in some senses I did go to university.

When I left school, I ended up at CAFOD, the Catholic development agency, with a clerical job in the fundraising department. I learned an enormous amount. My sister had also got a clerical job in an office. There was no question, looking back, that we were climbing the class ladder. That was very much what our parents wanted for us.

At CAFOD, I met Pat Gaffney, Dan Martin and Ellen Teague, all those folks who drew me into the peace movement through Catholic Peace Action and other things.

I don’t think I would have got involved in this work without middle-class people encouraging me and equipping me. I met Stephen Hancock and Milan Rai. Even though we were unemployed, doley activists, we were doing research, we were learning to do leadership, organising campaigns, we were publishing things, we were involved in direct action. That was a very formative time. I learned to do research then.

I got a job at FOR, the Fellowship of Reconciliation, and then I went on to study – and I went to prison as well. I met Virginia, we got married and had children. Virginia and I pay a mortgage on a semi-detached house in Oxford. I’m very much the lucky one who managed to get grants or managed to get donations and I’ve been able to carry on with peace work. I suppose I imbibed enough middle-classness in order to not be frightened of asking for money.

BBC or ITV?

Culturally, I feel very working-class. I never, ever, listen to Radio 4. It doesn’t interest me. Everybody in the peace movement seems to listen to Radio 4 religiously, I just don’t understand it! I listen to Radio 2 or Jack FM. In my downtime, I watch a lot of TV, Gogglebox and things like that. Almost no one else seems to! Apart from other peace activists who come from a working-class background.

“You’re either X Factor or you’re Strictly”

My wife Virginia, both her parents had professional jobs. One of the things we laughed about is that she wasn’t allowed to watch ITV when she was a kid, and in our house we never watched the BBC. I guess the modern day version is you’re either X Factor or you’re Strictly! Middle-class people also use classical references that I just don’t know, and another cultural area I have absolutely no idea about is classical music.

I think a key thing is if you’ve grown up middle-class, or more than that, you have much more confidence than someone who hasn’t. It always feels like, for a middle-class person, when you were growing up, somebody whispered into your ear the secret of life and that gave you enormous confidence. We never got that. So I always feel unconfident, no matter where I am, even when people are saying: ‘You’re doing great work!’ I’m always suspicious of that. I don’t know whether that’s a personality trait or whether it’s a product of class or culture.

With middle-class people, there’s the niceness factor. You can’t be angry. There’s a group meeting or a committee meeting, some one is being difficult. Nobody wants to say: ‘You’re being bloody difficult, stop it.’ Nobody likes confrontation. At the same time, I would own that I hate confrontation, I absolutely loathe it, but I do it when it’s necessary.