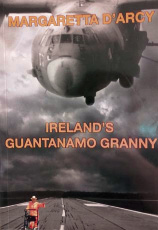

If there was ever a book that should be reviewed in Peace News this is it. Not only is 83-year old Margaretta D’Arcy a lifelong campaigner for peace but it was Peace News that drove her, at 79, to climb the fence at Shannon airport and protest on the runway – not once, but twice:

If there was ever a book that should be reviewed in Peace News this is it. Not only is 83-year old Margaretta D’Arcy a lifelong campaigner for peace but it was Peace News that drove her, at 79, to climb the fence at Shannon airport and protest on the runway – not once, but twice:

‘On the whole in the anti-war movement there was no real support for non-violent direct action. But then Peace News carried an article about an international week of protest against drones to coincide with World Peace Day on 21 September [2012]. We looked up the internet for arrivals and departures at Shannon to see if there was a window when no planes landed or took off, found there was a gap and we were on. We had discussed the possibility that the sky would not fall down and that no one would know and we decided we didn’t care. Part of the problem of the anti-war movement is fear of things falling flat. Humiliation. The press making us look ridiculous. To me failure is better than doing nothing.’

D’Arcy is an Irish actress, writer, playwright, and peace activist. She married the playwright John Arden when she was 23, and they worked and campaigned side-by-side until his death in 2012. His presence is felt within the book. They protested together at Shannon airport, and D’Arcy’s choice to continue her fight against the Irish state, while simultaneously fighting cancer, was her way of coping with the loss of her life partner. The book is dedicated to Arden, and it is full of characters, humour and drama – it even follows the structure of a three-act play.

It is also an excellent handbook for nonviolent direct action: ‘By wanting to have a conversation with the Irish State on the use of Shannon Airport as a transit point for the US war machine and its programme of extraordinary rendition, I became an enemy of mainstream society... By refusing to become complicit with war crimes by signing a bond, I had to be jailed. Sometimes to get change people need to become enemies of the mainstream.’

The book documents her defence (she represented herself in court) and her relationships with the other prisoners in Limerick and Mountjoy jails. It is illustrated with newspaper clippings, photographs of protests and messages of support: ‘The prison officers are thrilled as sackloads of cards, letters and poems come flooding in. K and I open the envelopes and sort the letters and cards, trying to separate the ones that have sent me addresses so I can reply. The only problem is that the prison runs out of paper.’

D’Arcy is an inspiration to generations of peace campaigners. Whether this book motivates you to leap a fence and hold up an aeroplane, or simply to send a letter of support to a prisoner of conscience, it will give you the courage to take part in your own conversation with the state.

Topics: Activist history