Meticulously sourced and based on extensive primary research, this book recounts a neglected thread of queer history.

Meticulously sourced and based on extensive primary research, this book recounts a neglected thread of queer history.

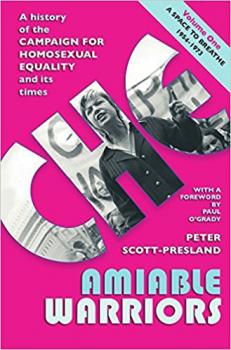

Scott-Presland states that he kept in mind the encyclopedic regimental histories which line the walls of the Imperial War Museum. Notwithstanding this militaristic metaphor, there is a great deal in these pages from which peace campaigners might learn. The Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE) was founded in 1964. At its height, it had 5,000 members and over 100 local groups. Nevertheless, it has been largely forgotten, losing space in the pages of queer history to more colourful, more confrontational groups. CHE’s cautious, some said reactionary, approach to societal change may seem out of step with our own times. Despite this, CHE’s activism built changes in public attitudes which 50 years later led a conservative prime minister to champion gay marriage.

CHE’s magazine, Lunch, was arguing the case as long ago as 1973: ‘The homosexual will always be a persecuted third-rate citizen until the following changes in our living pattern have been made: Legal marriages between those of the same sex ... Discrimination punished in a similar manner as racial discrimination is.’

This book constitutes a salutary reminder of just how brave people were to write to local newspapers in the 1960s and ’70s to call for equality, signing those letters with their own names. It is also a revealing case study of how a grassroots movement was built among homosexuals, beginning at a time when sex between men was still illegal.

CHE remains, by membership, the largest LGBT organisation these islands have ever known. It also had the courage to confront the class divide which permeates many political movements. In 1972, John Clearly, of the Wolverhampton group wrote: ‘What I want to do is to overcome this class barrier so that everyone will be accepted and treated as an equal and to attract the basic working class homosexuals into joining CHE.’

The first volume in a three- or four-volume history, A Space to Breathe: 1954-1973 is consciously not a work of queer studies. The author’s priority is to record what happened. It is also not an academic work, though it will prove valuable to academics.

Furthermore, it does not seek to rationalise or justify the attitudes of the time, but rather to step inside experiences which were different from those of today. As such it represents an archive of vivid, first-hand, oral history.

The weight of 600 pages, merely for this first volume, may deter some, but for readers with time and patience this is a valuable work.

Topics: LGBTQ+