Stephen Armstrong shows how consecutive governments have abandoned Britain’s most vulnerable citizens and overseen the gradual dismantling of a welfare state that once protected them. Importantly, Armstrong also tells the stories of those most affected.

Stephen Armstrong shows how consecutive governments have abandoned Britain’s most vulnerable citizens and overseen the gradual dismantling of a welfare state that once protected them. Importantly, Armstrong also tells the stories of those most affected.

Beginning with the 1942 Beveridge Report – the founding document of Britain’s welfare state – Armstrong outlines how, by adopting its recommendations, postwar governments were largely successful in eradicating what the report called the five ‘giants’ blocking the road of reconstruction: want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness. Today, 75 years on, these five evils have returned and, as Armstrong argues, many of those postwar achievements are now in ‘grave danger of being entirely undone’.

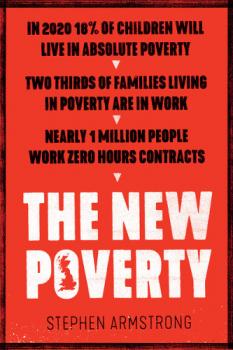

The statistics are shocking. In the UK, the world’s fifth-largest economy, there are now over 13 million people living in poverty, with an estimated one in five children living below the poverty line. Worse still, two-thirds of children in poverty live in a household where someone works. Work, Armstrong writes, is no longer a guaranteed path out of poverty.

The reasons? Armstrong points to decades of deregulation in the name of a ‘flexible labour market’, along with shady employment practices and adjustments to the benefit systems, which have left millions in low-paid, precarious employment. These folks drift in and out of the official definition of poverty each year – they are the ‘new poor’.

Blending statistical data and analysis with some truly horrific personal stories, Armstrong explains with great clarity how these new poor have the odds increasingly stacked against them, from the premiums they pay on energy bills and food shopping to the culture of debt engulfing them as a result of the financialisation of our economy.

Armstrong shows how the poorest are increasingly forced to rent homes in substandard and hazardous conditions. On health, he shows how unaffordable treatment has led to the gruesome rise of DIY dentistry and a ‘black health economy’. People in the poorest neighbourhoods now not only suffer longer GP waiting hours and generally poorer health, but they die, on average, seven years earlier than those living in affluent areas.

You cannot turn the pages of this book without feeling a visceral sense of outrage. With chapters on digital deprivation (the poorest 20 percent of the population lack access to the internet, depriving them of work opportunities and democratic participation), the socio-economic divisions across Britain underscored by Brexit, and the failure of our media to adequately report what’s going on, this is a timely book that deserves a wide readership. Highly recommended for all concerned citizens.

Topics: Social justice