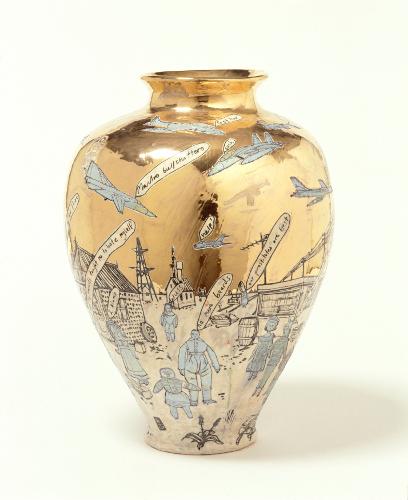

Dolls at Dungeness September 11th 2001 © Grayson Perry / Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro, London / Photo Stephen Brayne 2001 Glazed ceramic

I wonder whether people who have been directly affected by the aftermath of 9/11 – in a way that most of those viewing this exhibition haven’t – would find parts of it baffling or even insulting

For example, if you had lived in Baghdad during the 2003 war against Iraq, what would you make of the ‘twin towers’ created by Jake and Dinos Chapman? Nein! Eleven? consists of two tall piles of tiny, chopped-up Nazi soldiers, their guts spewing out around them. It is described by the Chapmans themselves as ‘two piles of disappointment and rot’.... It’s trite and reductive and I suspect only found its way into the exhibition because the curators needed a few big names.

Likewise, Dolls at Dungeness September 11th 2001, by Grayson Perry. He made it before 9/11, and after the event added fighter aircraft and speech bubbles to the dolls cavorting around Dungeness: ‘Eat shit motherfuckers’; ‘Go on kill yourself for a virgin fuck’; ‘Capitalist pigs’. Maybe I’m missing something very profound here, but it felt puerile and pointless, as if Perry thought he should make some comment on the event, but didn’t want to make the effort of doing anything meaningful.

For me, this was the crux of the problem with this exhibition: it felt like it was built around a few ‘star’ artists who essentially had nothing to say. Which is not to say that some of the 50 exhibits weren’t worth seeing. I was fascinated by Tony Oursler’s film, 9/11, shot in New York City in the immediate aftermath of the attack on the twin towers. I didn’t have time to see it all (there are far too many, too-long video exhibits) but I was struck by the peddlers who hit the streets almost immediately with US flag hats, badges, and trinkets. Terror is good for sales, as any arms company would no doubt agree.

Divided into four sections (9/11 itself; state control; weapons; and ‘home’), it is only with the last of these that we finally meet a few artists from countries we’ve waged war on over the past few years.

Hanaa Malallah’s My Country Map explores her ‘feeling of being trapped by the consequences of the Iraq wars’. Cities are positioned randomly with names burned into canvas, reflecting the destruction and fragmentation caused by the wars. In the short film White House, Lida Abdul methodically whitewashes the ruins of a presidential palace in Afghanistan. It’s a powerful comment on the truths of war, and how the narrative is set by the victor.

Pakistani artist Mahwish Chishty’s Drone Art ‘juxtapos[es] cultural beauty with the war on terror’. Her paintings show the silhouettes of drones decorated with traditional Pakistani ‘truck art’. They’re things of both beauty and terror, illustrating how drones have become just another feature of the landscape, like decorated trucks. The war on terror, normalised.

There are few voices of artists from countries attacked under the aegis of the war on terror. I’d have liked much more: to know what it means to live in those countries, to experience the much more potent state terror that we’ve inflicted and how that translates into art.

While it may be irksome to have to take off your shoes and be patted down before boarding an aircraft (Jitish Kallat’s Circadian Rhyme 1), it’s probably less so than cowering in a basement while a US bomber circles overhead.

This exhibition felt like a missed opportunity: what the IWM bills as ‘the first major exhibition to consider artists’ responses to war and conflict since 9/11’ could have been so much better. Get rid of the puerile, male, self-centred responses to 9/11, and give us more women, more voices of people living under the bombs. And, maybe, charge a little less: £15 is a lot even for the best exhibition, and this one really isn’t that.