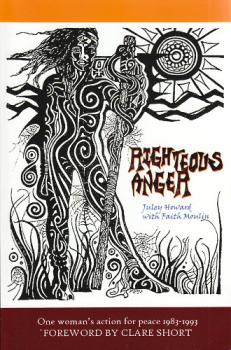

This book is a singular account of a community of action which didn’t just witness history, but was instrumental in changing it: Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp. 25 years on, life experiences can be forgotten, so I am grateful to Howard and Moulin for collecting these reminiscences for posterity.

This book is a singular account of a community of action which didn’t just witness history, but was instrumental in changing it: Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp. 25 years on, life experiences can be forgotten, so I am grateful to Howard and Moulin for collecting these reminiscences for posterity.

Like the film Pulp Fiction, this book begins at the end – with an action in 1993 where 16 women climbed into the grounds of Buckingham Palace to condemn nuclear testing in the Nevada desert. And, like Adrian Mole, the author uses her teenage diaries to document her life at Greenham Common.

Juley Howard was born into an ‘ordinary’ working-class family in Rugby. She was 15 when the Falklands War politicised her, and the women’s anti-nuclear-weapons camp at ‘RAF’ Greenham Common drew her like a beacon. After a couple of day-visits, at 16 she spent her summer holiday at the camp, and she soon became a long-term peace camper.

As a student at Reading University in the early 1980s, I attended ‘Embrace the Base’ protests at Greenham, but I still learned much from reading this account. For example, I had no idea that, thanks to the bailiffs, camping at Greenham often didn’t involve tents! On the other hand it did involve religion, rats and an awful lot of knitting.

Reading this book, we watch as a remarkable young woman evolves into a committed peace campaigner, with chapters covering life at the camp and camp politics, including sexual politics: ‘We had long debates about sexuality which ultimately led to the usual realisation that nobody really agreed about anything apart from the fact that Cruise missiles were wrong.’

The camp’s relationships with the American soldiers and the British judicial system were just as important: ‘In a way, the absolute adherence to non-violence at Greenham helped to keep us safe. The MoD police at the base knew us well and knew what to expect when arresting us, so generally they didn’t over-react…. The proximity of our lives to men, soldiers, police, weapons seems to be about vulnerability in the face of aggression, but we did not allow ourselves to be vulnerable. We took the initiative to be the aggressors.’

The camp is placed in its international context with accounts of Juley’s travels to – and actions in – Europe and the Americas. She even visits Libya as a guest of Libyan leader colonel Muammar Gaddafi where she gets into trouble for refusing to stand to pay respect to a dead terrorist.

This book helped me to re-live and re-evaluate an important decade. I appreciated the appendices including the timeline, and I enjoyed it both as a personal account and as a historical document. I salute Juley Howard and her fellow peace campers for their comfortless years at Greenham and their continuing political engagement.

You can purchase the book and find more information and source materials at: www.mygreenhamcommon.co.uk

Topics: Activist history