The spectacle of thousands of predominantly young people taking to streets in nonviolent protest against the threat of climate catastrophe is reminiscent of the mass demonstrations and sit-downs of the anti-nuclear Committee of 100 in the 1960s.

Like Extinction Rebellion (XR), the Committee – as indeed the broader anti-nuclear movement – was a response to an existential threat to civilisation, possibly even to human survival.

Like XR, the Committee was committed to using mass nonviolent direct action to achieve its objectives. In the case of the Committee of 100, the goals were the unconditional renunciation by Britain of nuclear weapons, and worldwide resistance to the threat of nuclear war.

The Committee was an attempt to put on a mass footing the methods of nonviolent sit-downs, occupations and other forms of disruption – in addition to more conventional rallies and marches – which had been pioneered by the Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War (DAC). (DAC organised the first Aldermaston March over Easter 1958 and adopted Gerald Holtom’s iconic nuclear disarmament symbol.)

Pledge to act

In July and August 1960, on the initiative chiefly of Ralph Schoenman, a US graduate student studying in England, a small group from New Left, anti-nuclear and pacifist circles began meeting informally.

They approached and secured the support of well-known writers and public figures including the philosopher Bertrand Russell, and the anti-apartheid campaigner reverend Michael Scott.

The upshot was the formation in October 1960 of ‘The Committee of 100’, launched with a declaration by Russell and Scott, entitled Act or Perish, which called for a ‘movement of nonviolent resistance to nuclear war and weapons of mass destruction’.

“The Committee attempted to put on a mass footing the methods of nonviolent sit-downs, occupations and other forms of disruption

which had been pioneered by the Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War.”

As its name implied, the Committee comprised 100 people, including well-known figures in the British postwar literary revival – John Arden, Margaretta D’Arcy, John Osborne, Shelagh Delaney, Robert Bolt, Christoper Logue and Arnold Wesker among them.

A key element to the Committee’s strategy was that planned demonstrations would not go ahead unless at least 2,000 pledges to participate had been received in advance.

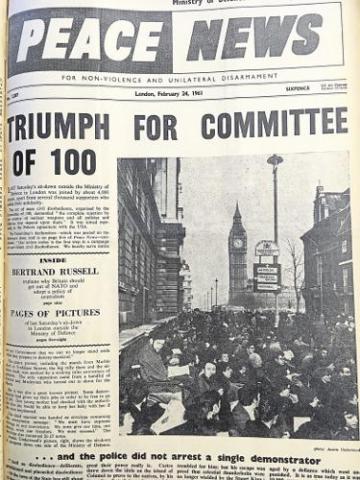

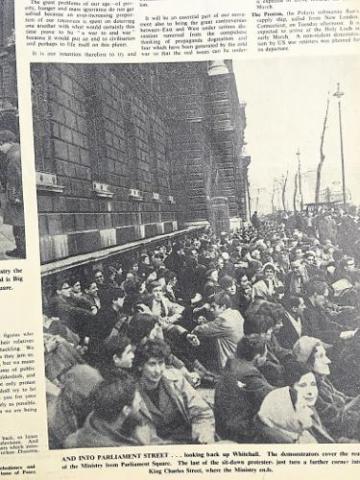

The Committee’s first demonstration, on 18 February 1961, was a sit-down by several thousand demonstrators outside the ministry of defence in Whitehall in central London. (Estimates of the numbers involved vary widely; the Committee itself claimed it was around 4,000.)

There were no arrests. After several hours, the 89-year-old Russell led the demonstrators back up Whitehall in triumph. The demonstration made the front pages of several Sunday newspapers and the publicity was generally favourable.

1,300 arrests

Further demonstrations followed in what proved to be the Committee’s most dynamic period.

Numbers were down by about a half on the second demonstration on 29 April – an attempt to hold a ‘Public Assembly’ in Parliament Square – but the event was saved, at least in terms of the publicity it generated, by the arrest of 800 people who sat down in Whitehall when the police blocked the way to Parliament Square.

When the Committee announced another public assembly in Parliament Square to take place on 17 September, the authorities reacted forcefully.

They invoked the Justices of the Peace Act of 1361 to summons 37 members of the Committee to appear before Malborough Street magistrates court.

At the hearing, 35 Committee members who refused to be ‘bound-over to keep the peace’ were sentenced variously to one or two months’ imprisonment.

“A key element to the Committee’s strategy was that planned demonstrations would not go ahead unless at least 2,000 pledges to participate had been received in advance.”

Among these were Bertrand Russell and his wife, Edith, Michael Scott, and a number of the well-known Committee members.

The authorities also invoked the 1936 Public Order Act to impose a ban on the demonstration in Trafalgar Square that was to take place on 17 September before the public assembly in Parliament Square.

The Trafalgar Square demonstration went ahead nonetheless and a total of 1,300 people were arrested and charged with obstruction.

At a simultaneous sit-down demonstration at the Polaris nuclear missile submarine base at Holy Loch in Scotland, 351 protesters were arrested.

Repression

Emboldened by its success, the Committee called for 50,000 to take part on 9 December in civil disobedience demonstrations in seven locations across the country – at bases in Wethersfield, Ruislip and Brize Norton, and in city centres in Cardiff, Bristol, York and Manchester.

By this point, the Committee had radically decentralised its structure and this was reflected in the geographical spread of the protests.

However, the day before the demonstrations, all six staff members of the national Committee were arrested and charged with conspiracy to contravene the Official Secrets Act.

The attorney general, sir Reginald Manningham-Buller, also announced that anyone who took part in the Wethersfield demonstration could face being charged under the Official Secrets Act.

That threat no doubt accounts in part for the fact that just a few hundred people turned up for the demonstration at Wethersfield, and an estimated total of 4,000 people in demonstrations across the country.

This was an impressive number in comparison to earlier DAC demonstrations but disappointingly short of the numbers the Committee had called for.

A total of 800 people were arrested.

The trial of the six Committee of 100 office staff under the Official Secrets Act constituted in itself a well-publicised demonstration.

The prosecuting counsel was the attorney general himself, and among the witnesses for the defence were Russell (who insisted ‘I want to incriminate myself’), archbishop Roberts (the former Catholic archbishop of Bombay), and the distinguished physicist and inventor of radar, Robert Watson-Watt.

All six were convicted though with a jury recommendation of leniency. Five were sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment; Helen Allegranza, the welfare secretary, received a 12-month sentence.

Winding down

The 17 September demonstration turned out to be the high point of the Committee’s mass civil disobedience demonstrations.

After 9 December, the Committee did organise further actions including a sit-down in central London in March 1962 at which 1,172 people were arrested.

Several thousand people also took part in a protest in London at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. But the dynamism and optimism of the earlier actions was missing.

A planned sit-down for 9 September 1962 outside the Air Ministry in London was called off when the numbers pledged to participate fell far short of the 7,000 minimum target set by the Committee.

“Some saw civil disobedience as a quasi-revolutionary strategy leading through a succession of increasingly large demonstrations to a mass uprising and the emergence of some kind of anarcho-pacifist society.”

In November, Russell resigned from the organisation and in the course of the year so did several of its best-known members.

In its later years, until its dissolution in 1968, the Committee’s demonstrations were generally on a smaller scale, several of them at bases or nuclear research establishments – more akin to the earlier DAC actions.

The Committee also widened its goals, taking on issues such as opposing the visit of king Constantine and queen Frederica of Greece to London in 1963 and promoting squatting in response to homelessness.

And XR?

What experiences of the Committee of 100 might be relevant to Extinction Rebellion and kindred movements today? I am reluctant to be too categorical on this issue as the context today is different in several respects.

First, nonviolent direct action, thanks to earlier campaigns, from DAC to Greenham Common, has became more widely accepted as a legitimate form of protest in the context of a parliamentary democracy.

This probably makes it easier for people to consider engaging in it but also means it has to be more dramatic and sustained to have an equivalent impact.

Second, the nature of the climate threat is somewhat different from that of a nuclear war.

For the latter to occur, a deliberate decision has to be taken by some government(s) to use nuclear weapons – and this is true even of a war that is initially sparked off by an accident.

Today, with the climate/ecological crisis, inertia alone, and a consequent failure to take internationally-concerted action, is sufficient to lead to catastrophe.

Third, the fact that some of the consequences of climate change and wider environmental disasters are already with us, from the Australian bush fires to the melting of the ice caps, may justify actions which would be ruled out as misjudged and counterproductive in less extreme circumstances. It may also provide the incentive for Extinction Rebellion and related movements to persevere.

One question which arises is why the Committee of 100 folded after eight years whereas CND remains in existence today.

One partial explanation may be the widely divergent views within the Committee about how the civil disobedience campaign would achieve the goal of nuclear disarmament.

For Russell, it was essentially a means of publicising the gravity of the crisis – as well as putting pressure on the government.

Others saw it as a quasi-revolutionary strategy leading through a succession of increasingly large demonstrations to a mass uprising and the emergence of some kind of anarcho-pacifist society.

But Britain was not on the brink of that kind of revolution, as indeed some in the Committee argued, and this became clear as the size of the demonstrations diminished.

Moreover, as noted earlier, the DAC and the Committee set a new benchmark for what was considered legitimate in terms of radical protest in this country, and civil disobedience began to be taken up by other movements and campaigns on both nuclear and other issues.

Indeed, CND itself, whose leadership had opposed the creation of the Committee of 100 and had initially considered its civil disobedience campaign as profoundly mistaken, agreed at its annual conference in 1981 to support ‘considered non-violent direct action’ and stated that it would ‘be willing to organise and lead national direct action if the occasion arose.’

Explainable

There is a final point I would make in connection with the Committee’s strategy and tactics, which I think is also relevant to Extinction Rebellion.

The Committee’s demonstrations were easier to explain and justify where there was a clear reason for the disruption being caused, whether this was blocking a military base, a nuclear weapons establishment, or an administrative facility like the ministry of defence.

Similarly, in the case of Extinction Rebellion, demonstrations such as obstructing airport expansion, or disrupting fracking, seem to me to be more likely to be understood and to be effective than, for instance, simply bringing city centres to a standstill or disrupting a regular commuter train service.

This point fits in with the broader argument about strategy and tactics put forward by Daniel Hunter in The Climate Resistance Handbook (extracts from which appeared in PN 2632 – 2633) and discussed by Gabriel Carlyle in his article, ‘How can we win?’ (PN 2634 – 2635).