Over a third of women in the world suffer physical or sexual abuse at some point in their lives, writes one of the contributors to this book.

For some, the resulting trauma leads to homelessness. While society reaches for easy narratives of deprivation and suffering, of the deserving and undeserving poor, the many circumstances that might lead a woman to homelessness are often ignored. These complex – often contradictory – attitudes are the subject of this book.

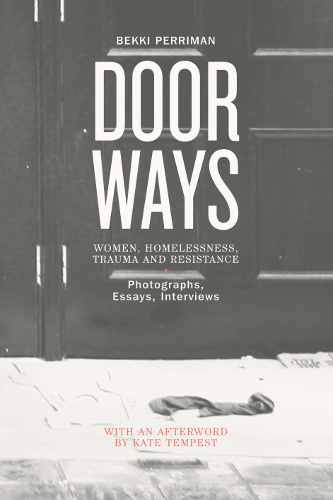

Firstly, this is an artist’s book, in which the artist Bekki Perriman, using a cast of contributors, builds on her own work in order to question the role of art in depicting the experience of homelessness.

Two series of photographs, ‘Where I slept last night’ and ‘Doorways’ show familiar landmarks such as St Martin-in-the-Fields and Charing Cross bridge reflected in puddles, as well as the doors of West End theatres and churches.

In a large-scale work, the Doorways Project, the artist installs audio tapes of interviews with homeless women in public doorways, the kind of spaces that might have been used by homeless people.

The women’s stories tell of the extreme danger of living on the streets, of daily humiliation and boredom, of mental ill health, and of drug and alcohol addiction.

They tell of the kindness and sense of community the women also find there, while stressing the difficulty of accessing services that are not really designed for them.

Perriman herself recalls feeling judged by passersby who seemed to assume that she was on the streets through choice.

Accompanying essays from female therapists, campaigners, academics and artists interact with the women’s stories to challenge common assumptions and attitudes.

Essays on the housing crisis and regeneration provide a context, in which we learn, for instance, of ‘defensible space’, a set of design principles originally intended to reduce crime, now frequently used in cities to deter ‘undesirables’.

Laura E Fischer’s essay on trauma provides a powerful understanding of why a woman might feel unsafe in a hostel, for example, or why she might use drugs and alcohol. She also tackles the way in which society’s reaction to trauma, which is often so physically damaging, is a ‘universal silence’ in which we are all culpable.

The final essay sees, in the resilience of street communities, creative resistance to ‘blind faith in progress’ and to a housing market that fails to provide homes for ordinary people.

The important question that this book repeatedly asks of contemporary art is whether it can move beyond communication of the lived experience of homeless women towards real action.