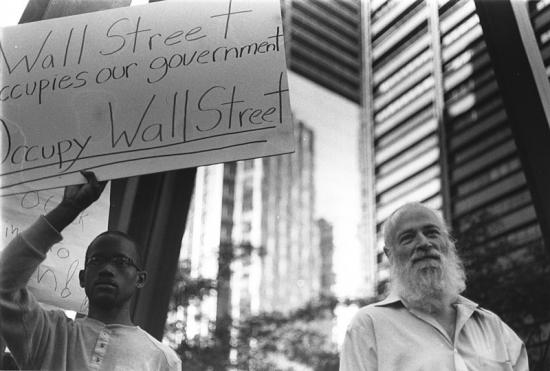

In this issue, we look at some proposals for cracking down on protest, from lord Walney, the government’s advisor on political violence and disruption, in his report Protecting our Democracy from Coercion (see here).

Walney doesn’t actually deal with the major forms of arm-twisting that interfere with democracy in Britain.

Walney doesn’t, for example, make any proposals for how to stop governments shutting down parliament when it suits them – as when Boris Johnson illegally ‘prorogued’ the Westminster parliament in August 2019.

Walney doesn’t make any suggestions on how we could stop governments instructing courts on the nature of reality, as with The Safety of Rwanda Act 2024, passed in April, which says that courts must rule that Rwanda is a safe country to deport asylum-seekers to, whatever the facts on the ground may be.

Walney’s report doesn’t tackle ‘the extensive creation and use of delegated law-making powers [which] has tipped the balance of power away from Parliament and towards UK ministers and other agencies to a worrying extent.’ Those are the words of the independent United Kingdom Constitution Monitoring Group, in a report published on 21 March.

Investor power

More important than all that, lord Walney’s report does not talk about the main limitation on democracy in a country like Britain: how elected institutions, from local councils to national parliaments, are pressured and coerced by business interests.

The most powerful lever big business has over the government is a ‘capital strike’, when companies refuse to invest (to open up new factories or offices, for example) or to operate at normal levels (they might stop hiring workers, for example).

The most disruptive version of a capital strike is ‘capital flight’, when investors pull their money out of a country, damaging its currency and shrinking the economy.

When François Mitterrand was elected as the first Socialist president of France in 1981, the French government carried out its manifesto promises.

It nationalised 12 big industrial companies and 38 banks, boosted welfare benefits and the minimum wage, put a wealth tax on individuals who had more than three million francs, and forced worker participation in decision-making on companies with more than 200 employees.

Many companies and investors either stopped a lot of what they were doing, or they began pulling their money out of France – at a rate of two billion francs a day.

All this wrecked the economy.

‘The withdrawal of funds provoked by investor displeasure, forced the eventual abandonment of much of the Socialist economic program,’ US economists Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis wrote in the New York Times in 1986.

This is the power of ‘the markets’, which has only grown with deregulation. This is the power that toppled British prime minister Liz Truss in 2022, not the civil service or the ‘deep state’.

There are less intense forms of coercion of democracy.

When Tony Blair was elected prime minister in a landslide in 1997, this seemed to put an end to the Tory era of ‘sleaze’.

Within months, however, the Labour leader had created a loophole in a new ban on tobacco advertising, allowing Formula One car racing to continue promoting smoking.

From documents released in 2008, we know that Blair intervened personally and repeatedly to force through the special treatment for Formula One (F1) after he’d met with the head of F1, Bernie Ecclestone. Ecclestone had given a million pounds to the Labour party months earlier – money that Labour was forced to return, eventually.

Corporate welfare

In the financial crisis of 2007 – 2008, billions were spent bailing out financial institutions.

These same banks had earlier pressured governments to deregulate their industry, then they’d gambled on risky investments in order to earn massive profits – but when their bad bets bankrupted them, they then coerced the government into covering the losses. Profits kept private; losses nationalised.

At its peak, British government financial support explicitly promised to banks went as high as £1.162 trillion, according to the national audit office, including £123.93bn of actual cash (making loans and buying shares).

The institutions that had failed so spectacularly, with such a destructive impact on ordinary people, were saved and they were allowed to carry on as they did before, with just a little bit more regulation.

A YouGov poll in the UK in 2018 found that: ‘More than seven in ten (72%) said that, from what they know, banks should have faced more severe penalties for their part in the crisis.’

Big money won, democracy lost.

Britain has experienced something like ‘corporate state capture’, according to Abby Innes of the LSE (London School of Economics, part of London University).

Innes wrote in 2021: ‘Britain’s neoliberal state has become a semi-permeable membrane in which governments refrain from intervening in the private sector but enable ever greater business access to public authority and revenue’ – with a third of central government spending being outsourced to the private sector.

There is an even deeper problem.

Elections and democracy, in a system like Britain’s, only affect our lives as citizens.

In our lives as workers, almost all of us have to put up with a totalitarian system of control where there is a little back-and-forth but, basically, we have to obey.

The idea of workers electing their managers, or having a say in what is produced by the company and how it is produced, is not even thinkable.

There is enormous coercion in the economy, and it cuts democracy completely out of the most powerful institutions in our society.

Lord Walney is not the only one who cannot see this.