PN: Judged by its impact on events, the anti-war movement played a fairly marginal role in the course of the First World War. Why have you chosen to foreground it in your history?

AH: I think traditionally people like to write books about movements that succeed, for example, the British anti-slavery movement which was the subject of my last book, but it seems to me that most movements that really matter fail a number of times before they succeed.

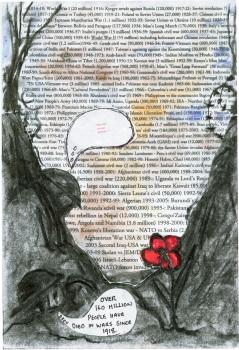

I would prefer to think of the movement to stop senseless and humanly-costly wars, not as a movement that failed in 1914-1918 but rather as a movement that hasnít succeeded yet. And despite the fact that these people didnít succeed in stopping the First World War, I find their stories enormously moving, enormously inspiring, and I think those of us that are working to stop wars today ought to be able to take some heart from it.

PN: One of the sections of your book that I found most exciting was your account of the anti-war group The No Conscription Fellowship (NCF). Before reading your book I had a picture of the anti-war movement as courageous but rather earnest and not very exciting, but this is a story of police raids and buried documents, and of the gleeful, even mischievous, appropriation of a pompous prosecutor's words to be used as anti-war propaganda. Can you give us a brief taste of this material?

AH: Well one of the nice things about these people is that they had a sense of humour.

There is this one episode you mentioned where in the course of a trial the prosecutor used the phrase "War would become impossible if all men were to have the view that war is wrong" and the activists put it on a poster, and then the government banned the poster, and so they suggested that the prosecutor himself be prosecuted because it was his words that they had put on the poster.

They said that if he was prosecuted and sent to prison they would do their best to look after his family, the way that they were doing for the families of thousands of conscientious objectors who were in prison. So I love that sense of humour.

Bertrand Russell, who to me is a great hero of this period, spent six months in prison for opposing the war, and his friend Lytton Strachey sent him the draft of the book Eminent Victorians to read while he was in prison. And Russell began roaring with laughter at some of the passages in this book whereupon a guard immediately reproached him, and said: "Prison is a place of penitence. You mustn't laugh here."

Well, these people laughed at a very dark time, and I honour them for it.

PN: Could you say something more about the role of women in the movement?

AH: Well, one thing that happened, of course, was that as the war progressed the men who were active in the No Conscription Fellowship were usually arrested and shipped off to jail.

So women ñ and keep in mind of course that this was a time when women in Britain had inferior legal rights to men and couldnít vote ñ became more and more key figures in the organisation, including editors of its newsletter.

Emily Hobhouse - who is best known for her exposure of the British-run concentration camps during the Boer War - did an amazing thing during the First World War.

Without official permission from anybody, without telling anybody, she travelled to France, to neutral Switzerland, crossed into Germany, went to Berlin, went to see the German foreign minister, whom she'd known before the war, and talked about possible peace terms.

She explored this as much as she could, and when she went back to Britain she tried to see people inside the British government, but no one very high ranking would talk to her.

She was completely laughed off as an insane, hysterical, single woman, lone wolf diplomat and possible crazy. But in fact, during this war that killed more than nine million soldiers and probably an even bigger number of civilians, she was the only person who travelled from one side to the other and back again in search of peace.

PN: One of the key stories in the book concerns a group of war resisters who were shipped to France and sentenced to death. Could you outline what happened and explain why this story is so central to the book?

AH: In the spring of 1916, the British government had set up a system for alternative service for conscientious objectors. You could work in a war industry, you could drive an ambulance at the Front, but they hadn't figured out what to do with people who refused this alternative service and did not want to be part of the war machinery even in a non-combatant role.

The first batch of these people - there were several groups which together totalled almost 50 - were automatically and forcibly conscripted into the army, and, when they refused orders to get trained, they were put into military prisons.

And then several of these batches of men, again totalling about 50 people, were transported across the English Channel to France, and were told: "You are going to be taken to a combat zone, and in the combat zone the penalty for disobeying orders is death".

There are some accounts from these first groups of men who were taken to a parade ground in ranks, and given the order: "Forward March". All the other soldiers assembled there marched off as directed. These people remained standing in place.

So they were put in prison on a punishment diet of just a few biscuits and water each day, and they believed that they were at risk of death if they kept to their convictions.

As their train had passed through London [on their way to France] they had tossed a message out of the window hoping that someone would find it, saying what was happening to them. They didnít know who might have found this message but in fact a sympathetic rail worker had found it and had contacted the No Conscription Fellowship. So people were working frantically in England, trying to save these men's lives.

Meanwhile, one of them managed to smuggle another message to England from the punishment barracks where they were being held, telling people to tell their families where they were. He did it in a very clever way.

Every soldier was given something called a Field Service Postcard, and there were something like eight messages that could be underlined or crossed out on the back of the card. And when censors saw these Field Service Postcards they realised that it wasnít something that they had to read because one could only underline or cross out these fixed messages. Well, this man very cleverly crossed out letters in the messages and managed to get the name of the port where they were being held - Boulogne in France - to their supporters in England.

And the No Conscription Fellowship then immediately dispatched a couple of clergymen to Boulogne.

Finally, the first group of these men is called before an assembly of a large number of soldiers, and their sentences are read out to them. The government had targeted four of them as ring-leaders, because the authorities in situations like this can never believe that there is a whole group of people doing something together out of their convictions. It is always a couple of trouble-makers who are the leaders.

So they had targeted four men, and the first one was called in front of this large assembly of soldiers, who could see that the word "Death" was written on the top on the paper that the officer was about to read from. And the officer read off the sentence, saying: "So-and-so is sentenced to death for disobedience". Then he paused and said: "sentence commuted to 10 years penal servitude by order of general sir Douglas Haig".

What the men didnít know was that their supporters had been organising frantically in Britain. Bertrand Russell had led a delegation of people to see the prime minister and had told him, you must see to it that these men do not die. And the prime minister, Asquith, had sent a secret order to Haig saying, donít shoot these conscientious objectors, send them back to England and we will take care of them in civilian prisons here - which was what happened from that moment on.

But to me it was an extraordinarily moving moment because here were people who were willing to risk death for their conviction that they shouldn't kill their fellow human beings.

PN: You've suggested that your last book (Bury the Chains) could spur activists into thinking about planning on much longer time scales than theyíre used to. What lessons do you think activists can draw from To End All Wars?

AH: Well, I got a message the other day that there is a newspaper published by the folks involved in the Occupy Wall Street protests in New York, called The Occupied Wall Street Journal. They just contacted me over the weekend and said, would I write an article for them?

So I'm trying to write an article talking about the anti-slavery movement as a model of one of these long struggles. We canít expect Wall Street to collapse and fold up and change its ways instantly, any more than we could expect this of the slave owners' lobby 200 years ago, or the war machine that existed 100 years ago, and still exists today.

Struggles to change these things are inevitably going to be long but the first moment of that struggle is looking around and seeing that there are hundreds of thousands - or millions - of people who feel the same way as you do. And that is certainly what we have got going on with the Occupy movement right now, and itís what the anti-slavery movement had going for it over 200 years ago.

In the First World War, it was much harder because warfare always tends to suppress dissent, to bring out feelings of patriotism and loyalty to oneís country, and of course when oneís country is invaded, as was the case for France and Belgium, itís almost impossible to get an anti-war movement going. So there wasnít that sense of looking around and thinking: "There are millions of people who feel the same way as I do."

Right up until the moment that the war began in 1914, that was the case, and Kier Hardie, whom I talk about in the book, was deeply convinced that, with ten million Socialist voters in Europe, Europe would never go to war. But he was proven wrong. It broke his heart and I think it was one of the reasons he died at such a young age in the second year of the war.

PN: We're rapidly approaching the hundredth anniversary of the war's outbreak. What role do you think the peace movement should try to play in this?

AH: Well, you know, anniversaries are good times to talk about the lessons of history, and I do feel the war was an unmitigated disaster, and that so many tragedies of the 20th century sprang from it.

It is almost impossible to imagine the Second World War happening without the First World War. And I think if ever there was a war that should have been stopped in its tracks it was the war of 1914-1918. Especially as it wasnít fought over any great principle. It broke out through this curious chain of almost accidental events beginning with the assassination of archduke Ferdinand at Sarajevo.

Up to that point in time, even though it was a period of some imperial rivalry and rising military spending, the countries of Europe were getting along with each other quite well together, Germany was Britainís biggest trading partner, nobody publicly claimed a piece of anyone elseís territory.

So I think this was a war that didnít have to happen and that pursuing it to the bitter end not only killed a vast number of people but made much more likely the horrible consequences which did indeed flow from it.

So I hope the peace movement can take the occasion of this anniversary - and I'm sure itís going to be marked in stages for four years - to emphasise this point again and again and again.