While the world was aggressively preparing for the First World War between 1900 and 1914, many people and organisations in Britain and Europe were boldly campaigning for peace. This is not generally remembered because that war destroyed so much, even the memory that many people had tried to stop it happening.

While the world was aggressively preparing for the First World War between 1900 and 1914, many people and organisations in Britain and Europe were boldly campaigning for peace. This is not generally remembered because that war destroyed so much, even the memory that many people had tried to stop it happening.

So amongst the military and political pressures of preparing for war, with its Boer War inadequacies, Dreadnought battleship-building, Baden Powell boy-scouting and much more, there was also a multitude of peace actions. These were by individuals, organisations, faith communities and even royalty. Destined to fail at the time, they laid the peace groundwork for the century to follow.

There were already peace societies and actions during the 19th century, but a quantum leap was now required. National and international organisations and people in Britain and elsewhere played their part, and many of their legacies continue today.

Organisations

One of the first was, perhaps surprisingly, ‘Politicians for Peace’. This was an ‘Interparliamentary Union’. Its 1889 co-founder, Liberal MP William Cremer, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1903 for this and other work. It is still going, now mostly on democracy issues.

The International Peace Bureau started in 1891. This Geneva-based organisation has continued throughout the 20th century, and is very active today.

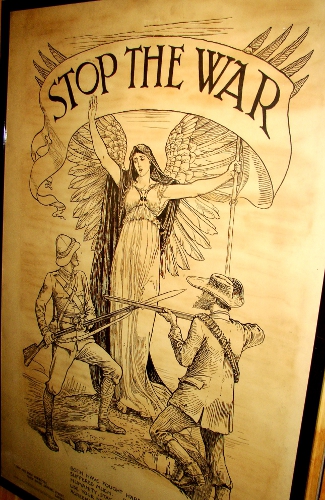

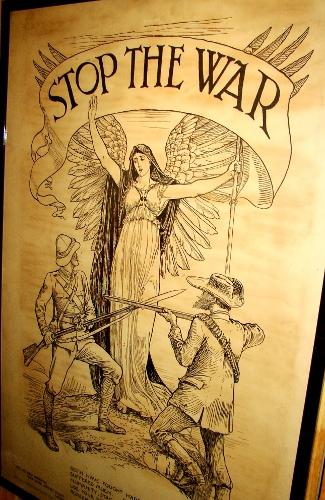

An early ‘Stop the [Boer] War’ campaign produced a poster to that effect around 1900. Shades of the same title!

The Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907 are well known. There was to be a third, in 1915. A century on, there was a campaigning conference of the same name and in the same place in 1999.

The British National Peace Council started in 1908 and continued until 2000. The Network for Peace then took over its co-ordinating activities.

Quakers have always been active in peacework, not least Isabella Ford of Leeds, particularly with the Northern Friends Peace Board’s formation in 1913. (It had a centenary conference in June this year.)

The Fellowship of Reconciliation (FoR) commenced in 1914, and continues today. (It has a centenary conference in Konstanz, Germany, next year.)

There were many Anglo-German Churches Exchange visits in 1908. The Co-op Holidays Association developed similar exchanges, especially from Yorkshire.

The International Peace Palace at The Hague was completed in 1913. Mainly financed by the US steel magnate Andrew Carnegie through his Endowment for International Peace, its purpose then, as now in its centenary year, was to arbitrate on matters of international law and justice. (There is a centenary conference this month, 2-3 September – see p16.)

The Church Peace Union was also financed by Carnegie, and started in 1914. It is now the Council on Ethics and Foreign Affairs.

Carnegie financed a Peace Yearbook in 1913, a forerunner of the current Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s (SIPRI) annual publication.

Individuals

Some individuals did their own thing, either by themselves or financed by others.

Some individuals did their own thing, either by themselves or financed by others.

Alfred Nobel, helped by the persuasion of the great Austrian peace campaigner Bertha von Suttner, left some of his great wealth for the Nobel Peace Prize, which was first awarded in 1901. The 20th century, devastating as it was, would arguably have been even worse but for the efforts of those who received his award.

Jan Bloch created the first International Museum of War and Peace in 1902 in Lucerne. In Britain the idea of such peace museums did not come to fruition until the mid-1990s, but now there is one in Bradford and over a hundred around the world.

In the first decade of the 20th century, king Edward VII became known as ‘peacemaker’ through influence with his royal relatives across Europe. He was, however, a military reformer too. [Furthermore, Edward had no qualms about using brutal force to maintain the British empire, which disqualifies him from the title ‘peacemaker’ – eds.]

Quaker Priscilla Peckover organised the Women’s Local Peace Association from 1879 for some fifty years from her home in Wisbech. She published and sent the Peace and Goodwill newsletter to over 30 British branches, and many internationally. The journal ceased with her death in 1931.

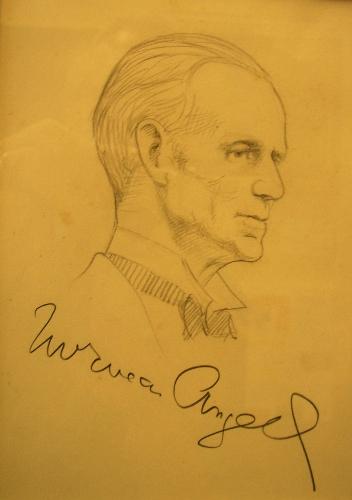

Norman Angell was by far the most well-known ‘peace person’ of the time in Britain. An author, he wrote The Great Illusion in 1910 which essentially said that war was bad economics. Such was its popularity it was reprinted or had a new edition 11 times in two years, and was published in 13 countries, including Germany.

More than thirty ‘Norman Angell Study Clubs’ were established across the country, although it was more a cerebral rather than a demo style of campaigning. A regular journal War and Peace was published. This was eventually absorbed into Contemporary Review, with the latter still continuing.

Any more?

There were doubtless many others and it will be good to hear of them.

There were no recorded mass demos during this pre-war time.

Inspiration

The era was a sudden and steep learning curve for the fledgling peace movement. But people didn’t give up, despite the ensuing carnage of people and of hope. That is perhaps the most important message.

In 2000, the great writer Elise Boulding used the term ‘The Two Hundred Year Present’ in which she said that what happened up to a century ago still affects us today, and what happens today will affect us for a hundred years in the future.

The early 1900 seeds sown by our peace ancestors were a vital experience for the rest of the 20th century. Using Boulding’s concept, we need to continue sowing new peace seeds to reach fruition over the 21st and into the 22nd centuries.