There’s plenty of weaponry in the Natural History Museum’s current exhibition, ‘Britain: One Million Years of the Human Story’, but no sign of any warfare.

For those, such as anthropologist Douglas Fry, who claim that ‘whereas homicide has occurred periodically over the enduring stretches of Pleistocene millenia [2.6m to 12,000 years ago], warfare is young... arising within the timeframe of the agricultural revolution’ (War, Peace and Human Nature, OUP, 2013) this is as it should be.

Indeed, according to Fry, ‘for over 99 percent of the time that the genus Homo has existed on the planet, about two million years, nomadic hunting-and-gathering has been the sole type of lifestyle’, and there are many features of such a lifestyle that are not conducive to warfare (see article opposite).

To be sure, these claims are contested. For example, Samuel Bowles, whose work Fry has critiqued, claims that ‘sedentary groups of... hunter-gatherers occupying coastal, riverain, and other resource rich sites... were common during the Late Pleistocene’ (126,000 – 12,000 years ago), and that there is evidence of ‘extraordinary levels of intergroup violence’ among such groups.

Whoever’s right, most, if not all, of the weapons on display at the Museum – which include a 400,000-year-old spear left by Neanderthals living in Clacton, one of the oldest spears in the world – were probably for use against animals, not people.

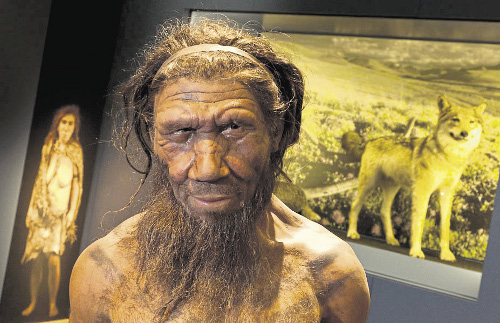

In her 1998 book, Blood Rites, Barbara Ehrenreich argues that ‘the roots of the human attraction to war’ may be found in the distant past when we were the prey, ‘decisively outnumbered by creatures far stronger and more vicious than ourselves’. And this exhibition certainly provides some vivid illustrations, at the gut level, of this latter reality: a world of lions, wolves, bears, hyenas and sabre-toothed cats (see photo).

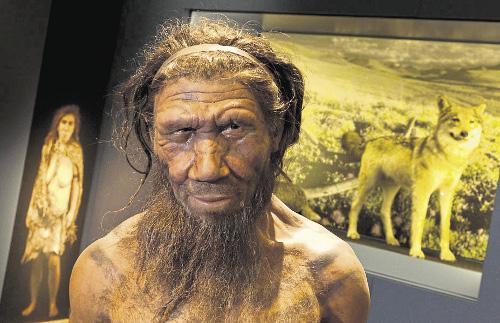

Yet, despite the many human fossils on display, the hands-on replica flint tools, the short films, and the stories of scientific detective work – all engagingly presented along a chronologically-staged journey through the last 900,000 years – the star of the show is undoubtedly the life-size model Neanderthal in the penultimate room (see photo): beautifully crafted by Dutch artists Alfons and Adrie Kennis, and so small! (The model homo sapiens, on the other hand, looks a slightly dodgy character.)

Interbreeding between homo sapiens and Neanderthals is known to have taken place, with recent research revealing that ‘2% of the genomes of people who descend from Europeans, Asians and other non-Africans is Neanderthal’ – making these resourceful, if mentally alien, people closer relatives to many of us than the ½ million year divergence between the two species might suggest.

The Neanderthals became extinct not long after the arrival of homo sapiens in Europe. Why remains unclear. Theories abound: from volanic eruptions to better mothering practices on the part of homo sapiens. And sure enough, there are some who have suggested that our ancestors’ ‘diseases, murders, and displacements did in the Neanderthals’ (Jared Diamond) in much the same way as European colonists exterminated scores of millions of Native Americans after 1492.

Rightly or wrongly, it seems, war and peace are never very far from our minds when we consider human origins.