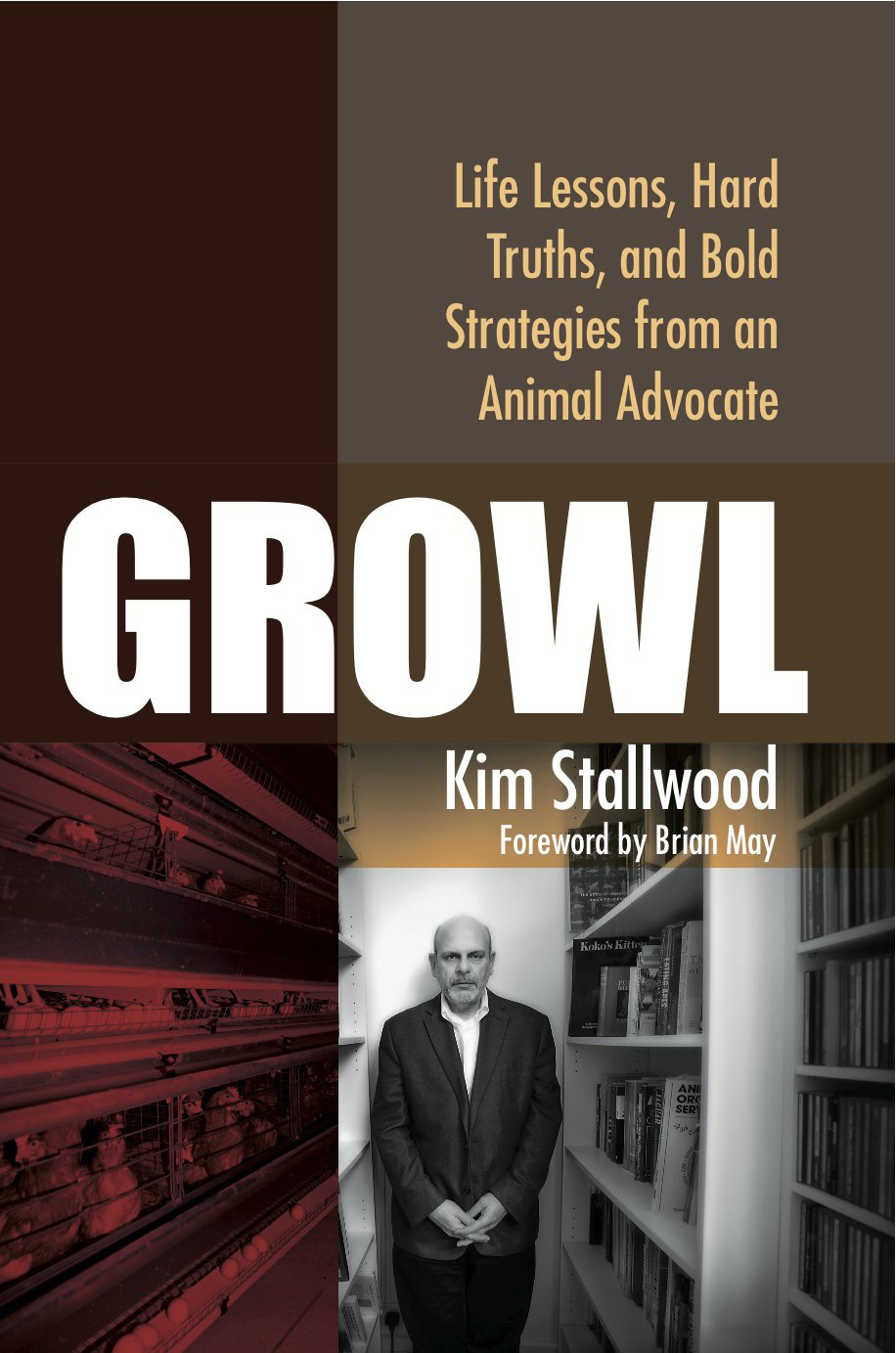

For 40 years, Kim Stallwood (sometimes known as ‘The Grumpy Vegan’) has been an active animal advocate. Growl combines autobiography, social history and an exploration of the philosophy and practice of animal rights. It is an engaging and readable book which made me draw parallels with other areas of nonviolent campaigning.After working in a chicken slaughterhouse, Stallwood became a vegetarian in 1974, aged 19. Two years later he became a fully-fledged vegan. Unlike today, when all supermarkets stock soya milk and dairy-free meals, being a vegan in 1976 took dedication and meant journeys to London’s Chinatown for tofu, as well as endless creativity with Sosmix.

For 40 years, Kim Stallwood (sometimes known as ‘The Grumpy Vegan’) has been an active animal advocate. Growl combines autobiography, social history and an exploration of the philosophy and practice of animal rights. It is an engaging and readable book which made me draw parallels with other areas of nonviolent campaigning.After working in a chicken slaughterhouse, Stallwood became a vegetarian in 1974, aged 19. Two years later he became a fully-fledged vegan. Unlike today, when all supermarkets stock soya milk and dairy-free meals, being a vegan in 1976 took dedication and meant journeys to London’s Chinatown for tofu, as well as endless creativity with Sosmix.

Soon after becoming vegan, the author began to engage with animal rights campaigning groups and his career as an activist, organiser, independent scholar and archivist began.

Stallwood worked for Compassion In World Farming (CIWF) and the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV) – transforming it from a staid organisation into a hotbed of radical activism – before moving to the US to campaign with People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA).

The four key values that are examined in Growl are compassion, truth, nonviolence and justice – values which are shared by most Peace News readers and anti-war campaigners. The author explores these themes and his own journey to becoming a genuinely compassionate activist. One of the concepts discussed in the book is that of ‘The Misanthropic Bunker’ (a place I‘m sure all passionate campaigners have some experience of). Stallwood describes it as a place of anger and hatred that vegans retreat to when the world of unremitting violence towards other animals becomes too much to cope with: “We’ll never achieve animal rights,” he tells himself. “Speciesism will never end. Animal rights will never be accomplished in my lifetime.”

Over the years, Stallwood learns that whilst there is a need for the misanthropic bunker to hide in once in a while, the way to avoid being consumed by hatred and intolerance is to exercise compassion and be kind to ourselves – and other humans – as well as to the non-human animals he campaigns on behalf of.

He explores a scenario where his pre-vegan self, ‘Kim the Chef’, is confronted outside the slaughterhouse by ‘Kim the Vegelical’ – waving a ‘Meat is Murder’ placard and shouting angry slogans: ‘In spite of their proximity and the fact that the conscience of Kim the Chef might have been unwittingly stirred by Kim the Vegelical’s protest, neither Kim is actually communicating with or seeing the other.’

However, Stallwood doesn’t dismiss angry protest as useless: ‘Remember. Compassion doesn’t have to be passive or even polite; compunction sometimes requires a rude awakening. Moral shocks are, by their very nature, unwelcome.’

While in his first job, at CIWF, Stallwood learns the importance of combining short-term goals with long-term objectives – CIWF’s goals are to end factory farming and promote ways to produce food that feed people directly. These pragmatic aims are not exclusive to vegans, but engaging with this campaign is often the first step to giving up eating animal flesh and becoming an animal advocate.

Throughout his long career as an animal campaigner, Stallwood has learned from the successes and failures of human rights campaigns. And 40 years of campaigning means that there are lessons to be learned – and experience to be fed back into the wider sphere of nonviolent action, making this an excellent resource for any nonviolent campaigner.

Topics: Animal rights