Last year, excluding suicides, over 13,000 people in the US – including roughly 2,500 children and teenagers – were killed by firearms. In 2012 – the most recent year for which comparable statistics are available – the number of gun murders per capita in the US was nearly 30 times that in the UK.

Last year, excluding suicides, over 13,000 people in the US – including roughly 2,500 children and teenagers – were killed by firearms. In 2012 – the most recent year for which comparable statistics are available – the number of gun murders per capita in the US was nearly 30 times that in the UK.

Yet, though ‘each individual death is experienced as a family tragedy that ripples through a community,’ notes Gary Younge ‘the sum total barely earns a national shrug’. Indeed, with the exception of mass shootings with large numbers of fatalities – such as the 17 June 2015 Charleston church shooting in which nine people were killed – these everyday killings ‘are white noise, set sufficiently low to allow the country to go about its business undisturbed.’

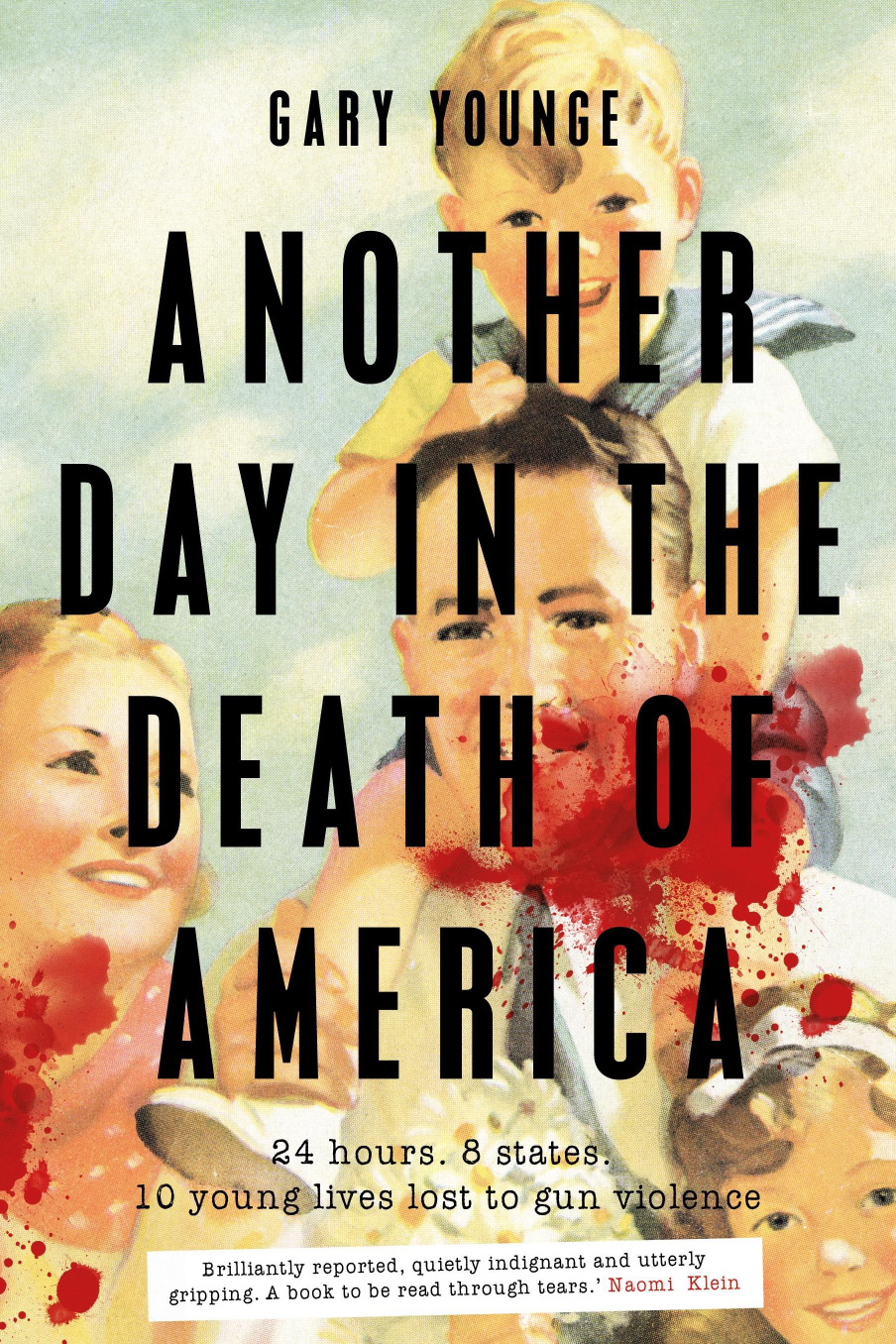

His latest book challenges this silence, telling the stories of 10 child and teenage gun deaths on a randomly-chosen Saturday in 2013.

Younge – who recently returned from the US after 12 years there as a journalist for the Guardian – spent 18 painstaking months tracking down, and where possible interviewing, anyone who knew the victims, ‘exploring the way they lived their short lives, the environments they inhabited and what the context of their passing might tell us about society at large.’

The result is as heartbreaking as it is revelatory.

Unsurprisingly, race and class are both a big part of the picture. Researchers have found ‘a clear correlation between the inability to find work and the propensity towards violent behaviour’, and African Americans are six times more likely to be incarcerated, twice as likely to be unemployed, and almost three times more likely to live in poverty than whites.

Of the 10 children and teens who died on the day in question, seven were black, two were Hispanic and one was white. All were working-class and male.

Drawing on journalism, scholarship and his own powerful sense of empathy, Younge provides acute insights into why such deaths receive cursory treatment by the media; the very different treatments afforded the youthful transgressions of the poor and marginalised and the rich and privileged; and the desperate struggles of black and Hispanic parents trying to bring up their children in areas ‘where schools are bad, gangs are rife, drugs and guns are easily available, resources are scarce and policing is harsh’.

‘While others are exerting themselves to get their kids into a decent college, through their SATs, or to excel at sports or music,’ he notes ‘these parents (who love their offspring no less) are devoting their energies to keeping their kids alive long enough for them to transition out of the neighbourhood, out of adolescence, or both.’

And whatever lengths they go to, these still may not be enough to save their children. Witness the death of 16-year-old Samuel Brightmon: shot dead while accompanying his friend on the short walk home to his grandmother’s house after a family night of drinking cocoa, playing Uno, and watching a film with his mother, friend and sister.

Younge also explodes a number of popular myths.

For example, the widely-held belief that African Americans are more likely to take drugs than any other racial group is false. In fact, white Americans are ‘considerably more likely than blacks to have ever used cocaine, hallucinogens, marijuana, LSD, stimulants such as crystal meth, and pain relievers including oxycontin’.

Likewise, it is not true that black Americans routinely abandon their children. In fact, ‘when children are under the age of five, black fathers are more likely to feed or eat meals with them, bathe, change their nappies, dress them and read to them daily than fathers in any other racial group, whether they live with their kids or not.’

As many guns as people

One of the crucial factors in America’s stratospheric homicide rate compared with other developed countries is the widespread availability of fire arms: with an estimated 300 million guns, held by about one-third of the population, there are almost as many guns in the US as there are people.

Though this is not a book about gun control, Younge explains the pernicious role of the National Rifle Association (NRA) in creating and maintaining this situation: stoking people’s fears of attack and violation; blocking laws that would make it illegal to store a gun in such a way that a child could easily access and fire it; and lobbying to prevent research into how to make people safe around guns.

However, he is also clearsighted enough to note that the elevation and canonisation of ‘worthy victims’ – such as the 20 school children fatally shot at the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut in 2012 – has led many of those most affected by gun violence, ‘the black, brown, and poor’, to eschew the gun control movement.

Surprisingly, despite all of these problems, it may not be necessary to wait until racism and poverty have been eradicated – or even for effective gun controls to be enacted – to stem the ongoing carnage.

In one section, Younge takes a car ride in Chicago’s South Side with members of Cure Violence – a project that treats violence like a contagious epidemic, employing teams of trained ‘violence interrupters’ and outreach workers – often ex-offenders and former gang members – to prevent retaliations, work with high-risk individuals, and mobilise communities to change norms around the use of violence.

Launched in 2000 in one of the most violent communities in Chicago, the project saw a 67 percent reduction in shooting in its first year. Its model has since been exported to some 52 sites in 23 cities across the US, as well as to projects in Latin America, Africa and the Middle East.

In his afterword, Gary Younge writes that researching and writing this book made him want to howl at the moon ‘for a wealthy country that could and should do better for its children... but appears to have settled, legislatively at least, on a pain threshold that is morally unacceptable.’ With former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg pouring tens of millions of dollars into building a nationwide grassroots network to curb gun violence it’s possible that legislative settlement might begin to shift.

This wise book will be a powerful tool in that ongoing struggle.