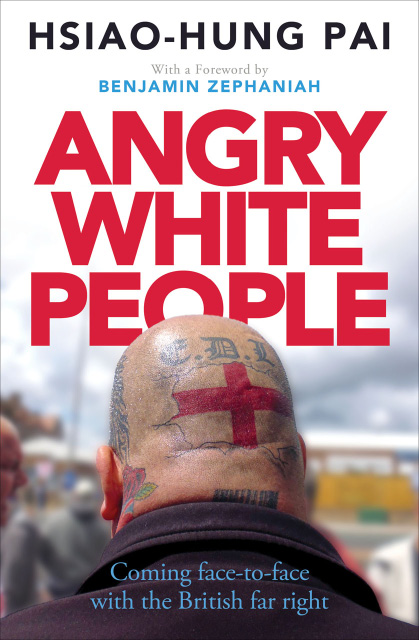

Hsiao-Hung Pai is a Taiwanese writer who has lived in London’s East End since 1991. Over three years she spent many hours interviewing far-right extremists and campaigners, often maintaining contact with them.

Hsiao-Hung Pai is a Taiwanese writer who has lived in London’s East End since 1991. Over three years she spent many hours interviewing far-right extremists and campaigners, often maintaining contact with them.

’Their faces on the TV screens and the front pages of newspapers show such deep anger, hatred and, above all, alienation, yet no explanation is ever given’, she writes. ‘Surely, I thought to myself, no one’s born a bigot. So what are the circumstances that have driven them to adopt such ways of thinking?’

The majority of the book is about the individuals who make up Britain’s far right – people who are seen at demos, fuelled- up and ready for a ruck – but whose stories are rarely heard. They are angry, marginalised and looking for reasons to blame for their poverty. Watching your home town change from a virtually- white monoculture to a multi-cultural community with a large Muslim population offers an easy target.

Many of those who Pai interviews have been involved with the English Defence League (EDL), which developed in response to a protest led by Muslims and other anti-war campaigners during a 2009 homecoming parade through Luton for the Royal Anglian Regiment. The protesters held up banners calling the soldiers ‘Baby Killers’, ‘The Butchers of Basra’ and ‘Cowards, killers, extremists’. Never under-estimate the power of a banner: this protest led to a series of attacks on British Asian residents in Luton, and fed the already-present anti-Muslim racial hatred there.

One of the most interesting characters she meets is a man called Darren whose nephew, Tommy Robinson, founded the EDL. A painter and decorator in his late 40s, and a former football gang leader, Darren took his son on his first EDL demo in 2009, carrying a ‘Black and White Unite & Fight’ banner. ‘We nearly got murdered – by half of Birmingham. On a football match, no one wants to kill you. They just want to beat you up. But on a political demo, they can kill you. I could hear the roar of the anti-racists, in the middle of a ghost town vacated by the police.’

In the early interviews, Darren is ambivalent about the EDL and his nephew’s leadership. The conversations with Pai seem to genuinely change his beliefs, leading him to reject the far right in favour of left wing politics.

In his foreword, the black British poet Benjamin Zephaniah says: ’I have always thought that these poor white people and these poor black people should unite and confront the people who oversee all of our miseries. It is classic divide and rule.... As long as people of colour and minority groups are seen as the other, as long as we are being blamed for all of society’s ills, we will keep trying to get our politicians to be honest, and we will continue to call on the white working classes to unite with us. But if they don’t, we will still have to fight them on the streets. This is personal.’

Rod Liddle panned this book in his Spectator review, but I think that is a reflection of his own misogyny, racism and... anger! Pai’s book is not perfect, but it is a valuable insight into the minds of people who choose to hate, and it offers hope that by keeping channels of communication open, positive change can arise.