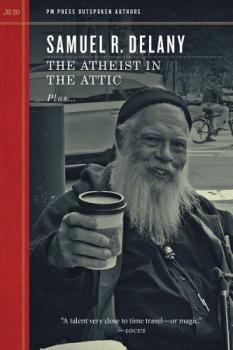

PM Press’s Outspoken Authors series continues with this showcase for the writing of the legendary science fiction (SF) writer and memoirist Samuel R. Delany, featuring the title novella, Delany’s famous 1998 essay ‘Racism in Science Fiction’, and an interview with Delany by series editor Terry Bisson.

PM Press’s Outspoken Authors series continues with this showcase for the writing of the legendary science fiction (SF) writer and memoirist Samuel R. Delany, featuring the title novella, Delany’s famous 1998 essay ‘Racism in Science Fiction’, and an interview with Delany by series editor Terry Bisson.

Clocking-in at seventy-two pages, The Atheist in the Attic centres on the famous November 1676 meeting between the philosophers Leibniz and Spinoza (the latter the atheist of the title) in The Hague, recounted here in the form of an (imaginary) written account by Leibniz. This is a strange but compelling work in which Delany foregrounds the social context of the pair’s meeting: the Dutch Republic’s so-called rampjaar (‘disaster year’) of 1672, in which England and France both invaded and a mob killed and mutilated two of the country’s most important political figures.

Nonetheless, apart from the obvious theme of elite fears of the underclass, the story’s broader political significance remained unclear to me. As for the philosophy, though I’d previously read a non-fiction book about the Leibniz-Spinoza meeting (Matthew Stewart’s The Courtier and the Heretic), I still found Delany’s account baffling.

The winner of innumerable awards (including four Nebulas and two Hugos), Delany is often referred to as the first African-American science fiction writer. However, Delany himself wears this label uneasily, noting, for example, that the African-American abolitionist, writer and soldier Martin Delany’s 1857 work Blake, or The Huts of America, which imagines a successful slave revolt in Cuba and the American South, ‘is about as close to an SF-style alternate history novel as you can get.’

Other precursors include George Schuyler, whose 1931 satire Black No More , featuring ‘a three day treatment costing fifty dollars through which black* people can turn themselves white’, got the jump on Dr Seuss’s The Sneetches by over 20 years. Schuyler’s story ends less happily (but more realistically) than Seuss’, with a gruesome account of the two white perpetrators of the scheme being lynched by a white mob ‘who believe the two men are blacks in disguise’. Delany, one of whose cousins was lynched, notes that Schuyler ‘simply used accounts of actual lynchings of black men at the time, with a few changes in wording.’

Recalling his own experiences of racism within science fiction, Delany recounts how, in 1967, three-months after his sixth sci-fi novel Babel-17 won the prestigious Nebula award, the famous SF editor John W Campbell, declined to serialise Delany’s new novel on the grounds ‘that he didn’t feel his readership would be able to relate to a black main character’.

These and other experiences led him to the conclusion that, permeable as it might sometimes seem, ‘The racial situation … is nevertheless your total surround’: ‘no matter whether the roof is falling in or the money is pouring in’, no one ‘will ever look at you, read a word you write, or consider you in any situation, without saying to him- or herself “Negro ...”’.

Racism, he maintains, ‘is as much accustoming people to becoming used to certain racial configurations so that they are specifically not used to others, as it is about anything else.’

Thus, while Delany often finds himself appearing alongside fellow African-American SF writer, Octavia Butler, he notes that during the active history of cyberpunk (an SF subgenre with a focus on ‘low life and high tech’) he was only once asked to sit on a cyberpunk panel, despite being widely acknowleged as a significant influence on the movement.

According to Delany, the only way to combat racism inside SF is ‘to establish – and repeatedly revamp – antiracist institutions and traditions’: actively encouraging the attendance of nonwhite readers and writers at conventions; actively presenting nonwhite writers with a forum to discuss their problems with conference programming; and ‘encouraging dialogue among, and … intermixing with, the many sorts of writers who make up the SF community.’