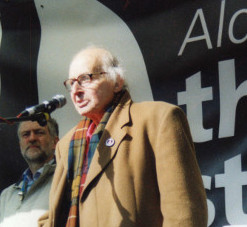

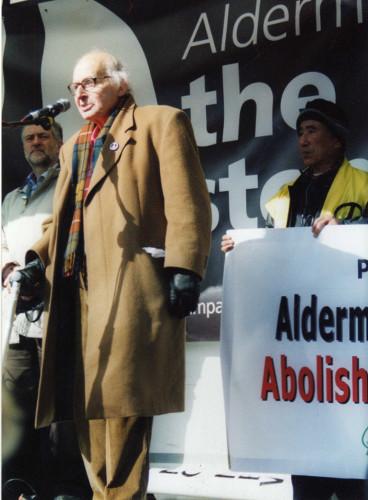

Walter Wolfgang died a few weeks shy of his 96th birthday, still campaigning for peace and justice. An organiser of the first Aldermaston march, Walter was vice president of both the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and the Stop the War Coalition at the time of his death.

Born in Frankfurt am Main, Walter had tasted anti-semitism first-hand by the time his parents sent him to Britain in 1937 to escape Hitler’s Germany. Walter made his home here. He became a British citizen in 1948 and joined the Labour Party the same year.

A devout Jew, Walter explained the connection between his religious and political views thus: ‘I came to understand the spiritual side of human existence through the Hebrew prophets. I was influenced by the idea that a society which doesn’t care for the disadvantaged ultimately decays and began to articulate the notion that western civilisation had taken a wrong turn. I believe that western civilisation has yet to be realised.’

Walter was deeply critical of Labour foreign secretary Ernest Bevin’s decision after the Second World War to align Britain with the United States. He campaigned for the adoption of a non-aligned foreign policy. Walter stood as a parliamentary candidate in the 1959 general election on a unilateral nuclear disarmament platform and increased the Labour vote in the safe Tory seat of Croydon North East.

More recently, Walter became known to a new generation of activists as the elderly gent evicted from Labour’s 2005 conference and detained under the Prevention of Terrorism Act for heckling another foreign secretary, Jack Straw, over the Iraq War.

Walter won instant approval for saying out loud what everyone else was thinking. His reinstatement to conference next day was greeted with a standing ovation and he was elected to Labour’s national executive a year later, where he continued to press the case for an independent, peaceful and non-nuclear foreign policy.

A modest man, Walter remarked: ‘I’m not very important and I’m certainly not a celebrity. But I’ve done a lot of things in my life that are important – considerably more so than getting thrown out of Labour Party conference, which isn’t very important at all.’

In an address to Walter’s funeral, his friend, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, described Walter as ‘an inspiring comrade, a brilliant mentor, a wonderful friend, and a huge loss to the international labour movement and the peace movement.’

I first met Walter in 1982, when we campaigned together against US cruise missiles in Britain. He became a special friend. The Walter Wolfgang I’ll remember was a man who always spoke truth to power.