The PN staff have each chosen their favourite books and films they read and saw this year. Here’s what we came up with!

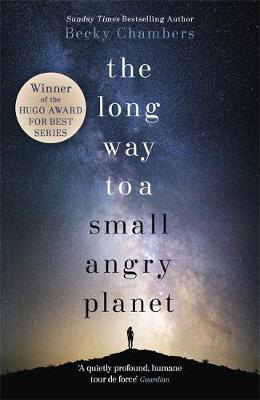

The best book I’ve read this year? Difficult one. How do you compare different genres? The most enjoyable was Becky Chambers’s The Long Way to a Small Angry Planet (Hodder and Stoughton, 2015, £8.99) and A Closed and Common Orbit (Hodder and Stoughton, 2016, £8.99).

This is two-thirds of her ‘Wayfarer’ trilogy.

It’s feminist sci-fi with great characters. Not so much space battles in spaceships (yawn), more relationships, friendships, inter-species politics in a fictional universe where humans are just discovering they are not the only sentient life forms (some of the sentient life forms are AI).

I’m thinking my daughter might like this so I’m getting her the three books for her birthday.

I am reading, for the second time this autumn, Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Artby Rebecca Wragg Sykes (Bloomsbury, 2020, £10.99).

It’s a round-up of all the palaeontological evidence to date that gives us a sight of the lives of some of our (European and western Asian) ancestors.

Did Neanderthals become extinct? No, they fell in love and had babies with Homo sapiens and other hominids.

It doesn’t matter that some of the science was beyond my grasp, I am excited that the techniques of seeing the past can reveal the dinner left on the plaque between their teeth of humans from 50,000 years ago and that family relationships can be read in bone.

All archaeologists look at their subject through the lens of their own politics and I am very happy that this rigorous science book is anarcho-feminist.

The evidence is that there was a time in human history when people didn’t hurt each other.

The Impostor by Javier Cercas (Hachette, 2018, £9.99) explores the real-life story of a man who claimed to have been a Republican soldier in the Spanish Civil War, a survivor of German concentration camps, and an anti-Franco activist.

On this reputation, he becomes a prominent trade unionist and campaigner for Holocaust awareness, but his story is exposed in 2005 as fraudulent.

Cercas explores what drove this man’s inventions as well as his own motivations and misgivings in writing about him. He ruminates in multiple moral and philosophical directions, detailing historical events and his complex response to ‘historical memory’ as Spain comes to terms with the civil war.

As a ‘novel without fiction’ exploring truth and motivation, this book is not straightforward. Despite attempts to shine a light from numerous angles, the truth may never be illuminated, but the benevolence of attempting to understand and the creativity of Cercas’ own mind is memorable.

Make up a sentence of at least 12 words, place quotes around it and plug it into Google. Almost certainly you’ll find no exact matches.

In Language Unlimited: the science behind our most creative power (Oxford University Press, 2019, £20), a wonderful work of popular science, linguist David Adger explains how syntax – ‘the invisible hierarchical structure of phrases and sentences’ that our minds automatically impose on the languages that we speak and sign – gives us this infinitely creative power.

Steven Pinker’s book The Language Instinct had a big political impact on me as a young person, highlighting, as it does, some of the amazing intellectual abilities that almost all us hold in common, simply by virtue of being human – and which we all too easily overlook or take for granted.

Hopefully, Adger’s short and well-written book can provide similar inspiration for others today.

Recommended for anyone with an interest in science and/or Chomsky’s work on language.

An atheist, my pick is an audiobook about religion I borrowed from the library: A History of the Bible: The book and its faiths, by John Barton (Allen Lane, 2020, £25). I was fascinated by the story of how the Bible came to be what it is – both the Hebrew Bible and the various translated Christian versions.

It had never struck me as weird before reading this that Christians decided at some point to include four inconsistent versions of Jesus’ life in the Bible. Why not just choose one? Or edit them together into a single authoritative gospel?

Barton points to evidence that early Christians saw the gospels just as convenient ways of collecting together Jesus’s sayings and actions, which is how they could cope with there being four different versions of his life.

It was only much later that Christians began to think of the gospels as divinely-inspired literal truth.

Films we saw in 2020

- Bending the Arc (documentary, 2017) The extraordinary doctors and activists whose work 30 years ago to save lives in a rural Haitian village grew into a global battle in the halls of power for the right to health for all.

- Woman at War (comedy, 2019) Can an Icelandic eco warrior/saboteur manage to stay a step ahead of the authorities – and adopt a child at the same time?

- Clouds of Sils Maria (drama, 2014) An actor (Juliette Binoche) confronts ageing and her young assistant (Kristen Stewart) in the mountains of Switzerland.

- Portrait of a Lady on Fire (drama, 2019) An aristocrat in late 18th-century France has a forbidden affair with an artist painting her portrait.

- Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners (documentary, 2020) How Britain as we know it was built on the profits of slavery, and slave-owners were compensated for the loss of their ‘property’.