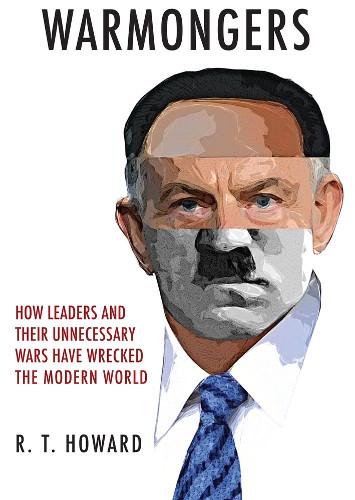

RT Howard is a writer specialising in intelligence and ‘defence’. His latest book looks at ‘individuals who were responsible for starting, conducting or extending an unnecessary war or show of force.’

RT Howard is a writer specialising in intelligence and ‘defence’. His latest book looks at ‘individuals who were responsible for starting, conducting or extending an unnecessary war or show of force.’

Echoing the broad tenets of ‘Just War’ theory, four examples of what constitutes an ‘unnecessary war’ are provided: the decision to pursue military force rather than diplomacy or negotiations; the use of excessive force; ‘war undertaken for no obvious reason’; and futile wars.

Beginning with the North American revolutionaries in 1774 and ending with king Salman of Saudi Arabia’s ongoing destruction of Yemen, he sets out a series of concise and readable indictments of warmongers.

Occasionally, information of interest to anti-war activists is highlighted. For example, he quotes US air force general Curtis LeMay’s estimate that US forces killed 20 percent of the North Korean population during the Korean War, while UK defence minister lord Gilbert notes: ‘I think the terms put to [Yugoslav president Slobodan] Milosevic at Rambouillet [in 1999 before NATO’s war in Kosovo] were absolutely intolerable… [which] was quite deliberate.’

The book is also a useful reminder that leaders throughout history have repeatedly deceived the public in their pursuit of war.

UK prime minister Anthony Eden’s duplicitous 1956 invasion of Egypt and US president Richard Nixon’s secret mass bombing of Cambodia and Laos are both included.

However, Warmongers is far from an anti-war treatise, with Howard concluding ‘there are occasions when war should and must be used’.

Somewhat strangely, Howard often provides his own advice on how a leader’s aims could have been achieved without resorting to full scale war – such as suggesting US president Ronald Reagan could have engendered a coup in Panama in 1989 or that it would have been better for North Korean leader Kim Il Sung to ‘destabilise’ the South Korea government in the 1950s rather than engage in military aggression.

Very lightly referenced with largely secondary sources, Howard’s thesis is seriously weakened by a frustrating focus on the foibles of individual leaders, rather than wider political, economic and social forces, including grassroots movements.

Eden’s and Napoleon’s warmongering is partly explained away by ill-health, while US secretary of state Madeleine Albright’s bullishness on Kosovo is put down to ‘traits’ originating ‘in her traumatic childhood’.

I would recommend anyone looking to understand international relations, especially the roles of the US and UK, to ignore Howard’s book and read the sharper, evidence-based analysis of British historian Mark Curtis and US dissident Noam Chomsky.