The sub-title of this book condenses a complex life into a compact haiku.

The sub-title of this book condenses a complex life into a compact haiku.

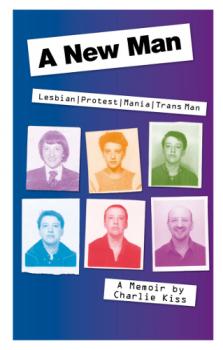

The author was born in London in 1965 to a Colombian mother and a father with Hungarian heritage. Charlie Kiss is his real name, but when he was born, his birth certificate identified him as female. He lived as a lesbian until his early 30s when he realised that he was transgender. It took until 2007 for him to complete his transition.

The early part of Charlie’s life saw him growing up playing with other boys, loving football (before girls were ‘allowed’ to play football), calling himself David and, by the age of 10, becoming sexually attracted to girls.

Charlie’s family life was unconventional, and not without challenges. His mother and father split up when he was four and he never had a good relationship with his stepfather.

He was given a surprising amount of freedom whilst growing up and by the age of 13, when the family had moved up to Yorkshire, he discovered the band Crass and was bunking off school to go to punk gigs in Liverpool.

By 16, Charlie was living independently and had become part of the lesbian feminist community in York – at the time of the Yorkshire Ripper. He travelled to London for anti-nuclear protests, where he was arrested and charged for the first time just after his 17th birthday in 1982.

Soon after this, Charlie visited Greenham Common for the first time (within the first year of the camp setting up). Three of the 22 chapters cover time at Greenham – and in prison as a result of actions at Greenham.

Like Juley Howard’s Righteous Anger (PN 2616 – 2617), this book is a valuable documentation of an individual’s experience of living at Greenham Common and of the counter-cultural movements of the 1980s and ’90s.

It is also fascinating because it looks back at the life of a strong individual who lived more than three decades before feeling comfortable with who they really were.

This is the story of an unhappy soul who took refuge in an all-women community only to realise that he was not a woman but the ‘enemy’. The journey was far from easy.

I found the descriptions of Charlie’s relationship (at 17) with a controlling 43- year-old woman disturbing – as were the tales of their successive unhappy relationships, alcohol abuse, the periods in prisons and hospitals, the psychotic episodes and the times on psychiatric wards.

Throughout, Charlie comments on instances of violence – whether instigated by women or men – and explores whether violence is exclusively a masculine phenomenon.

It is reassuring to see that his family, and one of his early girlfriends, Rebekah, were there to support him through periods of mental ill-health and through his transition. And it is also rewarding to learn from the epilogue that Charlie has now lived happily as a man for more than 15 years.

This is also a valuable book to read at a time when transition is such a polarising issue.

Charlie concludes: ‘I firmly believe that your gender should not stop you from doing anything you want; there should be more flexibility. Children should be free to develop without being forced into rigid gender roles.… You can of course be a masculine woman or a feminine man and everything in between – that doesn’t mean you are trans. Being trans is much more instinctual and about having a fundamental disconnect with your body.’

I have never felt a fundamental disconnection with my body, and in the past I have struggled to understand why anyone would feel the need to subject themselves to extensive and major surgery in order to feel happier. Charlie’s story helped me walk a mile in someone else’s shoes.

Topics: Activist history, Radical lives